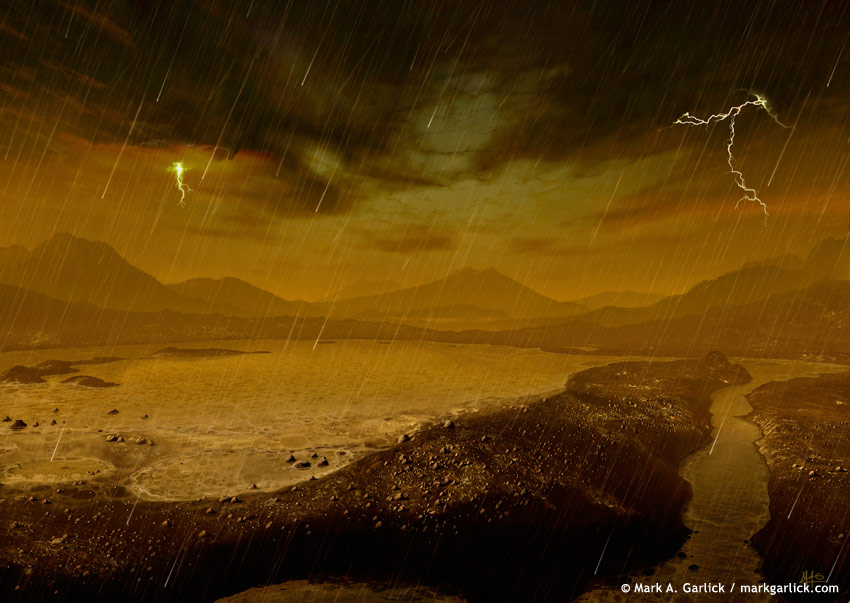

Mars is a dry, dusty place, with globe-girdling sand seas, mile-wide dust devils, and frequent world-wide dust storms.

In spite of the ubiquity of dust on Mars, though, the physics of dust-lifting and transport remain mysterious. For instance, the seasonal appearance of dark streaks on slopes across the surface of Mars, called recurring slope lineae, were thought to result from flow of brine. Recently, though, we’ve found they are more likely granular flow, but what exactly drives their seasonality is unknown.

Experiments conducted by the aeolian physics group at University of Duisburg-Essen has brought a little clarity to the mystery of martian dust.

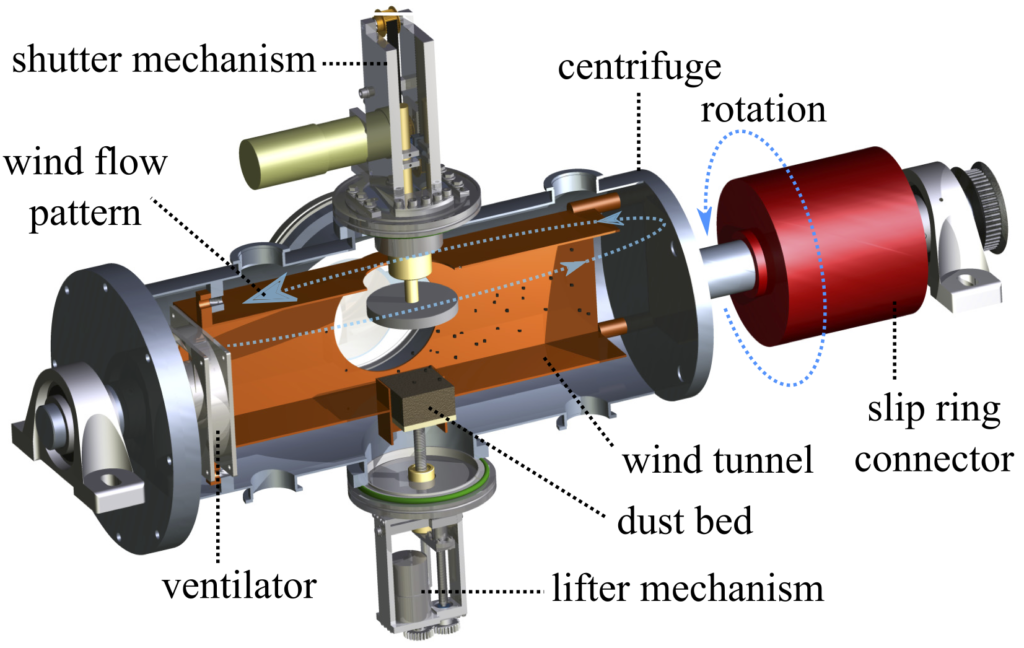

One of the biggest challenges for experiments exploring martian dust transport is replicating Mars’ low gravity (40% of Earth’s) and air pressure (10% of Earth’s). Since gravity and pressure help determine how winds move dust, accurate experiments must somehow create winds in a low-gravity environment under near vacuum.

To make a little pocket of Mars on Earth, Maximilian Kruss and colleagues took a small vacuum chamber centrifuge onto a “vomit comet” and conducted parabolic flights to create short periods of microgravity.

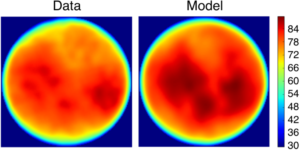

They filled the chamber with martian-like dust grains and turned up the fan to figure out when the winds were strong enough to start blowing the dust. By imaging the grain bed and tracking the grains, they estimated this threshold wind velocity, which is key to understanding when and where Mars can blow dust around.

Kruss and colleagues found, reassuringly, that theoretical models about dust transport were accurate. These results help us understand aeolian processes on a wide range of bodies, not only on Mars but any body with a low-pressure atmosphere.

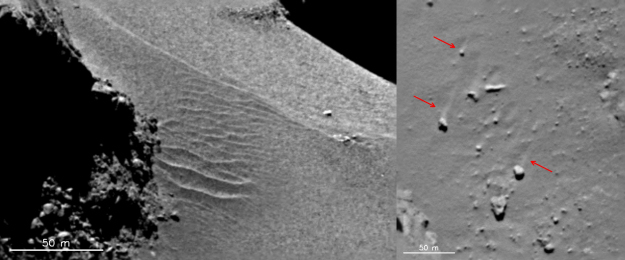

Indeed, even comets play host to aeolian processes. When the Rosetta Mission flew past comet 67P, it saw features on the comet’s surface that looked for all the world like wind streaks and dune fields.

Kruss and colleagues suggest dust transport may be important on some exoplanets, where gravities and atmospheric pressures span an even wider range than in our solar system. And so, these results, taken from a tiny vacuum chamber, may bear on processes on worlds across the whole galaxy.

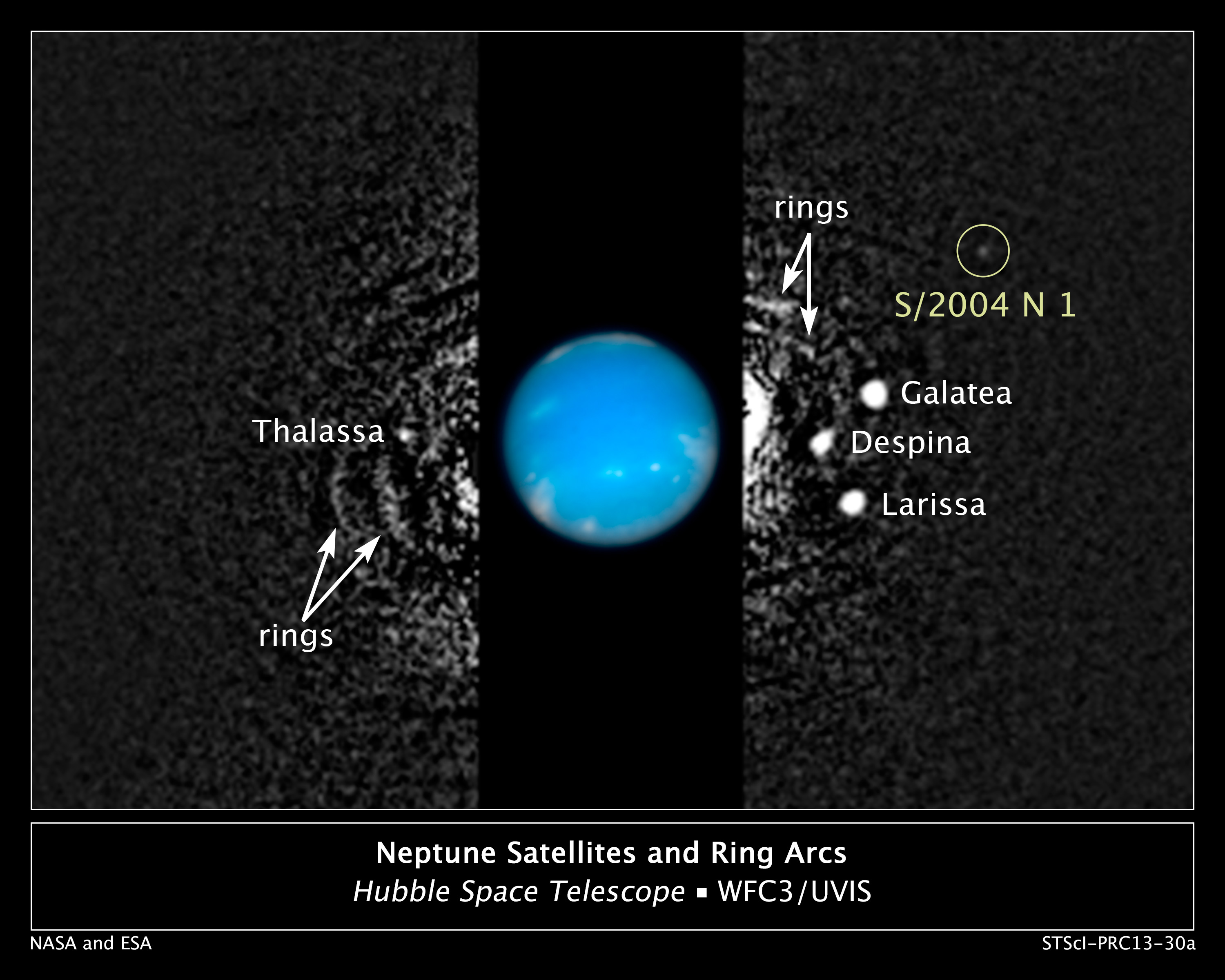

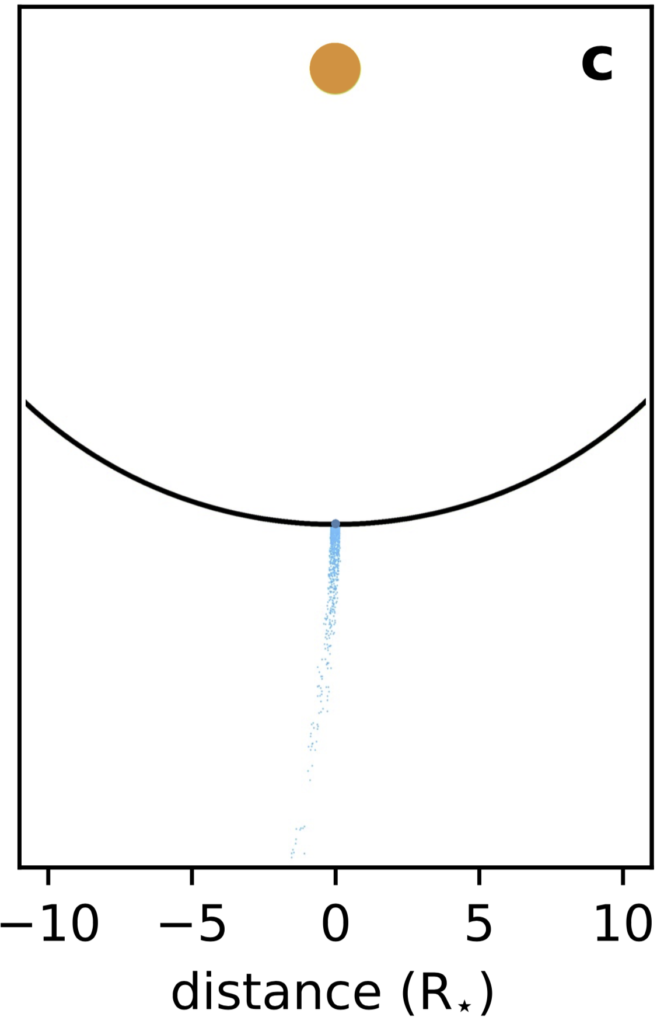

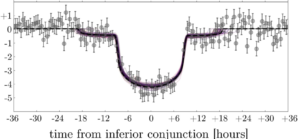

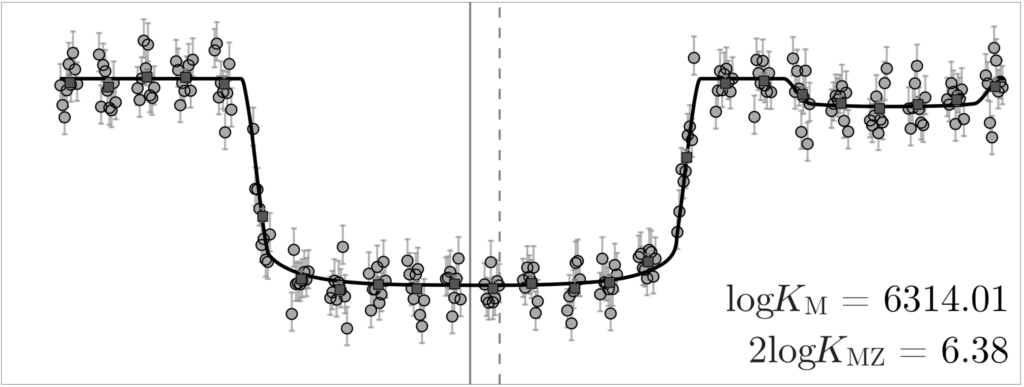

As always, more data are needed to corroborate this fantastic result, but if it holds up, Kepler-1625 would be a system with one super-sized Jupiter-like planet accompanied by a Neptune-sized moon which orbits at a distance of about 300,000 km, not too different from our own moon’s distance.

As always, more data are needed to corroborate this fantastic result, but if it holds up, Kepler-1625 would be a system with one super-sized Jupiter-like planet accompanied by a Neptune-sized moon which orbits at a distance of about 300,000 km, not too different from our own moon’s distance.