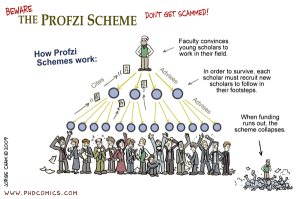

To say getting a job in academia is difficult is an understatement — a recent study showed something like one in 8 PhDs will manage to find a faculty position. Fortunately, the overall unemployment rate among STEM PhDs is low, less than 2%, so there’s lots of good alternatives.

To say getting a job in academia is difficult is an understatement — a recent study showed something like one in 8 PhDs will manage to find a faculty position. Fortunately, the overall unemployment rate among STEM PhDs is low, less than 2%, so there’s lots of good alternatives.

For myself, I was fortunate to have lots of support from family, friends, and colleagues, but the academic job search was excruciating. Usually the process of getting a faculty position involves a series of interviews, and among them, the phone interview was particularly stressful for me because it often lacked the non-verbal channel that constitutes a huge fraction of human communicative bandwidth — there’s nothing worse than interrupting one of your interviewers while they’re still trying to get a question out.

In prepping for my phone interviews, I came up with a few strategies that I’ve recently shared with friends who are currently applying for jobs. On the off-chance that they might be helpful generally, I’ve described them below.

Usually, the phone interview involves being asked a series of questions (sometimes scripted) from members of the hiring committee at the department to which you’ve applied. I found that I often struggled to come up with good answers on-the-fly, so, after a few poor performances, I wrote up answers to questions I’d gotten in previous interviews or ones I anticipated. Then I laid them out on tables in a circle around me in my office, so I could easily find an answer to a question, if asked.

I didn’t read the answers verbatim, but the notes were extremely helpful for keeping my answers concise. I found it very easy to ramble on, trying to find the words you think the committee is looking for.

Here’s my list of questions:

- “How do you think your research program would fit into the department? Who would you work with here?” I had already done extensive research on every faculty member before an interview, even those not in my field of astronomy. Not that you’ll work with them, but unless you’re interviewing with a department that specializes in exactly your field, you’ll probably have some folks from different fields involved with your interviews.

- “What classes could you teach?” For this question, I sifted through the course catalog so I could point to specific classes they already offered before suggesting new ones, but good chance they’ll ask about both kinds.

- “Why do you want to work here?” I tried to mention specific things about the school and department, not just answer “because you’re hiring”.

- “How will you involve students, grads and undergrads, in your

research?” I had one or two specific projects in mind, as well as thoughts about how I would support the students’ career development. - “What resources will you need to continue your research?” Especially important when I interviewed with smaller places that didn’t have all the resources of a larger place.

- “What are your public outreach plans?” In my case as an astronomer, I looked up and contacted local amateur astronomical societies to ask about what they were up to and how I might help if I came to town.

- “How will you fund your research? What specific funding programs could you apply for?” In my case, I’d already applied for several grants and served on grant review panels, so I had some specific ideas.

- “How would you fit into this town?” Especially important if you’re

interviewing for a job in a smaller town since they might be concerned you’ll get bored and look for a new job soon after arriving. - “Where do you see yourself in five years? What goals do you have for your research/funding/teaching?” Pretty standard, but good to have specific ideas about how your research/teaching might develop. Most people know you can’t know exactly, but they’ll be interested in your broad vision.

- “How will you balance teaching and research?” I got asked this one a lot, and it’s especially important to have an answer if you haven’t done much teaching before.

You should also have questions for the hiring committee:

- “How many students are there in the department? What happens to them after they graduate?”

- “What is there to do around town?/What’s the town like?”

- “How does the department fit in at the university? How supportive is the university of the department?”

- “Does the university and department have relationships or collaborations with other nearby schools?”

- “Where in town do faculty live?”

- “What is the timeline for hiring decisions?”

- “Where is the department going in the next few years?” Always fun to turn this question back around on the hirers.

If you’ve got any comments or corrections, please pass them along. Happy Holidays.

UPDATED – 2018 Dec 5:

The illustrious Laura Kreidberg (https://twitter.com/lkreidberg/status/1070389734432743424) suggested adding the question “How would you support students from diverse backgrounds and encourage inclusion in the dept?”. I could imagine that being asked by the interviewers or it might be a good question for an interviewee to ask to gauge a department’s commitment to equity issues.