A very active and engaging morning session on detecting exoplanets via the transit method on AAS 229 Day 1. Lots of good talks (although all of the talks were by male astronomers) and probing but polite questions (again, mostly by male astronomers – interesting study on these trends here). A few talks stuck out in my mind.

A very active and engaging morning session on detecting exoplanets via the transit method on AAS 229 Day 1. Lots of good talks (although all of the talks were by male astronomers) and probing but polite questions (again, mostly by male astronomers – interesting study on these trends here). A few talks stuck out in my mind.

Aaron Rizzuto from UT Austin looked for transiting planets in stellar clusters spanning a range of ages using data from the K2 Mission and found there seem to be fewer hot Jupiters in clusters 10 million years old than there are in older (hundreds of millions of years old) clusters. He suggested that this may mean it takes 100s of millions of years for the migration that makes hot Jupiters to take place. That would probably rule out one standard model for making hot Jupiters, namely gas disk migration, since that probably takes place within a few 10s of millions of years.

Dave Kipping of Columbia University discussed his search for transits of Proxima b, the recently discovered, Earth-sized planet just four light years from Earth. Unfortunately, the host star, Proxima, is a highly variable star due to almost constant flaring. As a result, it would be very difficult to see the planet’s transit – as Kipping said, it requires wading through “a sea of variability”. However, Kipping and his group struggled valiantly to recover the transit using data from the Canadian MOST satellite, and it looks like the planet just does not transit. So we probably won’t know the planet’s radius (at least not for a long time). Bummer.

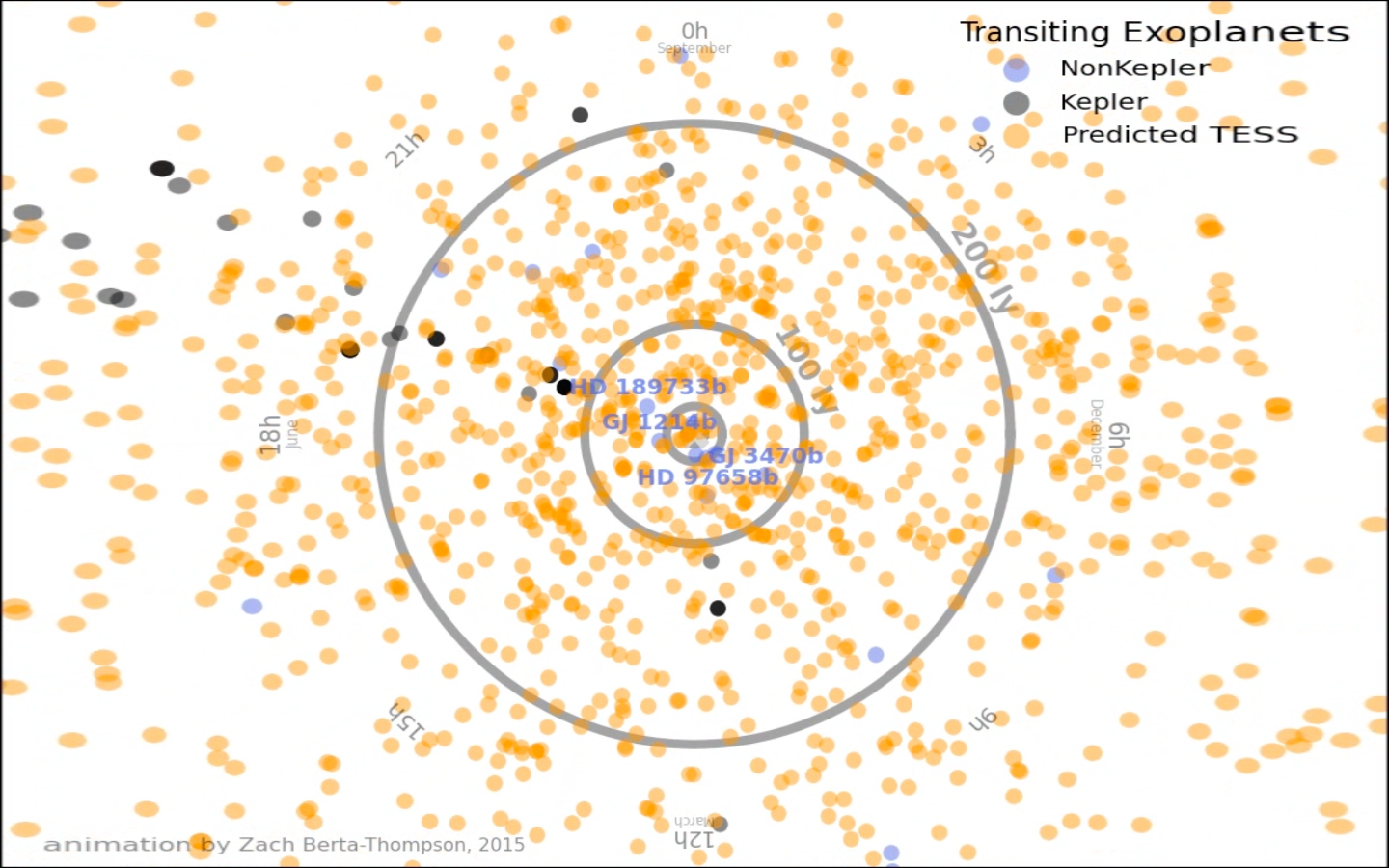

The last talk of the session was from George Ricker, the PI of the TESS mission, the follow-up mission to Kepler, about TESS’s status and prospects. Apparently, the mission will observe more than 2 million stars! Orbiting many of those stars will be nearby habitable planets, and Ricker showed an amazing simulation of where those stars might be found (courtesy of Zach Berta-Thompson of UC Boulder), a still from which is shown below.