Meetings

I’m sitting in the hotel lobby at the Woodlands Marriott, waiting for my supershuttle to IAH and recouperating from my second Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference, LPSC. Before I’m whisked away back to Boise, I thought to write about a few of the fascinating and mind-blowing things I saw this week.

First of all, LPSC is an annual conference that focuses on the geology, geochemistry, and geophysics of planetary science. There’s a lot of focus on solar system bodies with solid surfaces, as opposed to the annual DPS meeting, which has a bit broader focus.

I arrived on Sunday evening and dove immediately in, helping with the First-Timers’ presentation review, an opportunity for new-comers to the meeting to have more senior folks provide feedback on their posters or oral presentations.

Monday dawned cloudy, and I sat through several talks about our sister planet Mars. One that stuck out for me was one about field experiments to explain the perennially mysterious gully formations found on martian slopes with sleds of dry ice.

Tuesday saw me in a session on Saturn’s moon Titan, a cornucopia of geology and atmospheric physics. One particularly impressive talk discussed work to understand how methane deluges on Titan modified the surface.

Titan-Farnsworth: Analyzing spectral properties of regions that just received methane rain on Titan #LPSC2018 pic.twitter.com/YubU1Z9Hq9

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 20, 2018

Tuesday evening, I presented our group’s work flying drones through active dust devils.

Wednesday was packed with talks on sediment transport experiments and analyses, attempting to decipher the martian aeolian cycle, including a neat study of time-lapse imagery of martian dunes.

Aeolian Geo-Chojnacki: Beautiful animations of mobile dunes seen on Mars @HiRISE #lpsc2018 pic.twitter.com/q6kIV1aGHb

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 21, 2018

Thursday was packed with Pluto and results from New Horizons. One talk that stuck in my mind was an analysis of landslides on Pluto’s moon Charon, which, frankly, was a little bit of a tear-jerker. Hard to believe that not one hundred years ago, we didn’t even know Pluto existed. Now we’re trying to understand the system’s geology.

Pluto-Beddingfield: Landslides on Charon were low-friction and low enough energy that the ice probably did not melt in falling #lpsc2018 pic.twitter.com/MVaZ8U7nz4

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 22, 2018

Friday morning wrapped up the meeting with a series of talks about glacial geology on Mars, including a fabulous presentation on mysterious geomorphic features on Mars. Even though these features look for all the world like glacial flow, they appear on totally flat ground, where flow shouldn’t be possible.

Glacial Mars-@Shann0nMars: Strange flow-like features in valleys might represent ancient glacial flows #lpsc2018 pic.twitter.com/u721TzFN0c

— Brian Jackson (@decaelus) March 23, 2018

And now to catch the shuttle.

Using an Instrumented Drone to Sample Dust Devils

Dust devils are low-pressure, small (many to tens of meters) convective vortices powered by surface heating and rendered visible by lofted dust. The dust-lifting capacity of a devil likely depends sensitively on its structure, particularly the wind and pressure profiles, but the exact dependencies are poorly constrained. In this pilot study, we flew an instrumented quadcopter through several dust devils to probe their structures.

I just arrived home after a week-long visit to Aspen, CO to attend the Formation and Dynamical Evolution of Exoplanets Conference at the Aspen Center for Physics.

This conference was a cozy affair, with just over 100 attendees, and was narrowly focused on dynamical questions and approaches related to the origins and fates of exoplanet systems.

Researchers from around the world gave presentations on topics ranging from the dynamics of debris disks to observations of planet-hosting binary star systems. Blocks of presentations were punctuated by lengthy coffee breaks, when the real scientific give-and-take takes place. These interludes often give rise to groundbreaking, thesis-motivating, all-nighter-pulling research ideas.

Most of the presentations and conversations were excellent and inspiring, and I can’t do them all justice in a short blog post. So I’ll just talk about one that struck me in particular.

On Tuesday, Hanno Rein at Toronto spoke about a new N-body integrator his team has been developing in recent years, called REBOUND. This new framework may spur a revolution in dynamical modeling of astrophysical systems.

In astronomy, “n-body integration” is jargon for the numerical simulation of interactions among multiple (“n” of them) gravitating bodies. For hundreds of years, astronomers have been able to describe the orbital of two gravitating bodies quite easily, thanks to Johannes Kepler.

But as soon as you add another body to the system, there is no exact way to solve for the orbital motion of the bodies (except in very specific and limited circumstances). Even in the case of two bodies, if you want to include more complicated forces than simple gravity, solving for the orbital motion can be quite difficult.

To surmount these difficulties, scientists have turned to computer simulations to model in an approximate way the evolution of n-body systems. Although scientists have spent decades coming up with better and better models and algorithms, n-body simulations can still take a lot of computing power, and the often complicated codes can be cumbersome to set up and run. More than that, it’s often difficult or impossible for scientists to share results because there’s no good agreed-upon format for simulation output.

Rein’s REBOUND open-source code solves several of these problems at once: it employs latest modeling schemes to track orbital motions and gravitational interactions; it can be run using inside of an iPython Notebook; and it provides a uniform format for simulation output which anyone can use to re-run or re-analyze another scientists work – critical for scientific reproducibility. The iPython Notebook also provides a really neat visualization capability so you can directly watch the evolution of your astronomical system.

Time evolution of the orbits of stars in Leela’s constellation.

The code is so easy to run, in fact, that I installed and began running it immediately after Rein’s presentation. And all of its capabilities allowed me to finally simulate and visualize the evolution of a system I’ve wanted to look at for a long time – see animation at left (see here for how I created it).

I also gave a presentation on our group’s work looking at disruption of gaseous exoplanets.

And so, the combination of beautiful scenery and beautiful science made the Aspen Exoplanets conference one of the best in recent memory.

I’m sitting in my hotel room on the morning after the 2017 LPSC Meeting, trying process all the science that washed over me in the past week. And it was a lot, as you can see by checking out the twitter hashtag #lpsc2017.

From the migration of Martian dune ripples to the global seas on Enceladus, there’s no way for me to do it all justice in one blog post. So instead, I’ll talk about one of the talks that stood out most for me.

On the last day of the conference, Dr. Colin Dundas of USGS gave a mic-droppingly good talk in which he argued very convincingly that Mars’ recurring slope lineae are NOT the result of flowing water. This is a big deal for folks who study Mars but might sound a little arcane for non-Martians.

The animated image above consists of several pictures taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter over several months. The very pronounced dark streaks extending out from the cliff face – those are the recurring slope lineae or RSLs. In many locations on Mars, they recur from one year to the next; they always show up on sloped surfaces; and they are long lines. Hence recurring slope lineae.

The animated image above consists of several pictures taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter over several months. The very pronounced dark streaks extending out from the cliff face – those are the recurring slope lineae or RSLs. In many locations on Mars, they recur from one year to the next; they always show up on sloped surfaces; and they are long lines. Hence recurring slope lineae.

Under the current conditions at Mars’ surface, liquid water is not stable over long times, but these dark streaks sure look like small amounts of water running out over the surface, which got people very excited when they were first discovered.

In fact, just a few years ago, some scientists analyzed the spectra of some RSLs and argued they were highly salty brine flows. The salt is important because, even though pure water can’t exist on the surface of Mars, large amounts of salt can stabilize the water, at least for a little while.

This was a huge result, not just because it meant RSLs were small amounts of running water on Mars but because it raised the possibility of much larger sub-surface reservoirs of water. And where there’s lots of water, there could be life.

Well, Dundas’s talk throws all that into doubt. By analyzing the angles of the slopes on which the RSLs occur, Dundas showed that they almost every one of them ended on a slope of about 30 degrees.

Now, if RSLs are flowing water, they should keep flowing, even on small slopes. But if they are some sort of dry granular flow instead, you would expect them to stop once they reached the angle of repose, which is about 30 degrees.

Dark streaks on the sides of Martian dunes seen by HiRISE. These are NOT due to liquid water but resemble in many ways the RSLs.

To bolster his argument, Dundas showed several examples of dry granular flows on Mars that exhibited many of the same properties as RSLs – recurring dark streaks, running along sloped surfaces.

Continued work will either corroborate Dundas’s striking result or circumvent it, and given the number of folks lined up to talk with him after his talk, I’m sure the fans of liquid-flow RSLs will work hard to counter his arguments. And that’s how science progresses – one falsified hypothesis at a time.

Not quite as splashy, I also gave a presentation on our work trying to de-bias dust devil surveys. I’ve posted the presentation below.

All in all, my first LPSC was a great mix of science, warm weather, and warm friends.

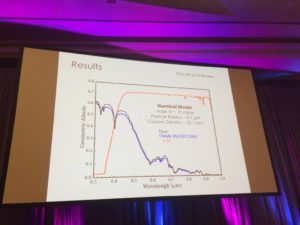

Figure from Gao’s talk, showing the spectrum of a planet before (blue and black lines) hazes and after (red line). The molecular features are almost completely wiped out by the hazes.

On day two of the AAS 229th meeting, I attended the morning session on exoplanet characterization and theory, which focused on atmospheric characterization. Several great talks, but one that made an impression on me was Peter Gao‘s presentation on sulfur hazes in hot Jupiter atmospheres.

Gao discussed work from Kevin Zahnle at NASA Ames showing that UV photolysis can transform even small amounts of gaseous sulfur in a hot Jupiter’s atmosphere into significant amounts of polymer haze. Something that has become a running motif in exoplanet atmosphere studies, these hazes discombobulate the spectrum of light emerging from a planet’s atmosphere, completely masking the signatures of other atmospheric components. This is bad news if, say, you wanted to determine the composition of a planet using light reflected from its atmosphere.

In the afternoon, I was fortunate to attend Sean Carroll‘s plenary talk “What We (Don’t) Know About the Beginning of the Universe”. It was a fascinating tour of all the different ideas about the origin of the universe, including The Big Bounce, baby universes hidden inside black holes, and the idea that the universe may have no beginning and no end. The best part of the talk, for me, was the end, when Carroll showed us a stern letter from a 10 year old skeptic sent to him in a response to an NYT article in which Carroll was quoted:

I Don’t know if you Exist But I Do! I bo not Agree with your Articl and I Do not Beleave that “MOMBO-JOMBO” if you do … Well! it’s Disturbing thought But I know How to Deal with it! I will Not let the Wolb Disiper under My Nose But if you Do I cant say I’m sorry!

Sincerely

a ten year old who knows a little more than some Pepeol!

George Wing

ps. some peopl Have a little to Much time.

Just brilliant!

Unfortunately, I had to depart for home shortly thereafter, so I’m missing the rest of the meeting. So here endeth my blog series on the meeting. Our fall semester at Boise State starts next week, though, and I plan to have weekly (maybe even semi-weekly) updates on the blog, so stay tuned.

A very active and engaging morning session on detecting exoplanets via the transit method on AAS 229 Day 1. Lots of good talks (although all of the talks were by male astronomers) and probing but polite questions (again, mostly by male astronomers – interesting study on these trends here). A few talks stuck out in my mind.

A very active and engaging morning session on detecting exoplanets via the transit method on AAS 229 Day 1. Lots of good talks (although all of the talks were by male astronomers) and probing but polite questions (again, mostly by male astronomers – interesting study on these trends here). A few talks stuck out in my mind.

Aaron Rizzuto from UT Austin looked for transiting planets in stellar clusters spanning a range of ages using data from the K2 Mission and found there seem to be fewer hot Jupiters in clusters 10 million years old than there are in older (hundreds of millions of years old) clusters. He suggested that this may mean it takes 100s of millions of years for the migration that makes hot Jupiters to take place. That would probably rule out one standard model for making hot Jupiters, namely gas disk migration, since that probably takes place within a few 10s of millions of years.

Dave Kipping of Columbia University discussed his search for transits of Proxima b, the recently discovered, Earth-sized planet just four light years from Earth. Unfortunately, the host star, Proxima, is a highly variable star due to almost constant flaring. As a result, it would be very difficult to see the planet’s transit – as Kipping said, it requires wading through “a sea of variability”. However, Kipping and his group struggled valiantly to recover the transit using data from the Canadian MOST satellite, and it looks like the planet just does not transit. So we probably won’t know the planet’s radius (at least not for a long time). Bummer.

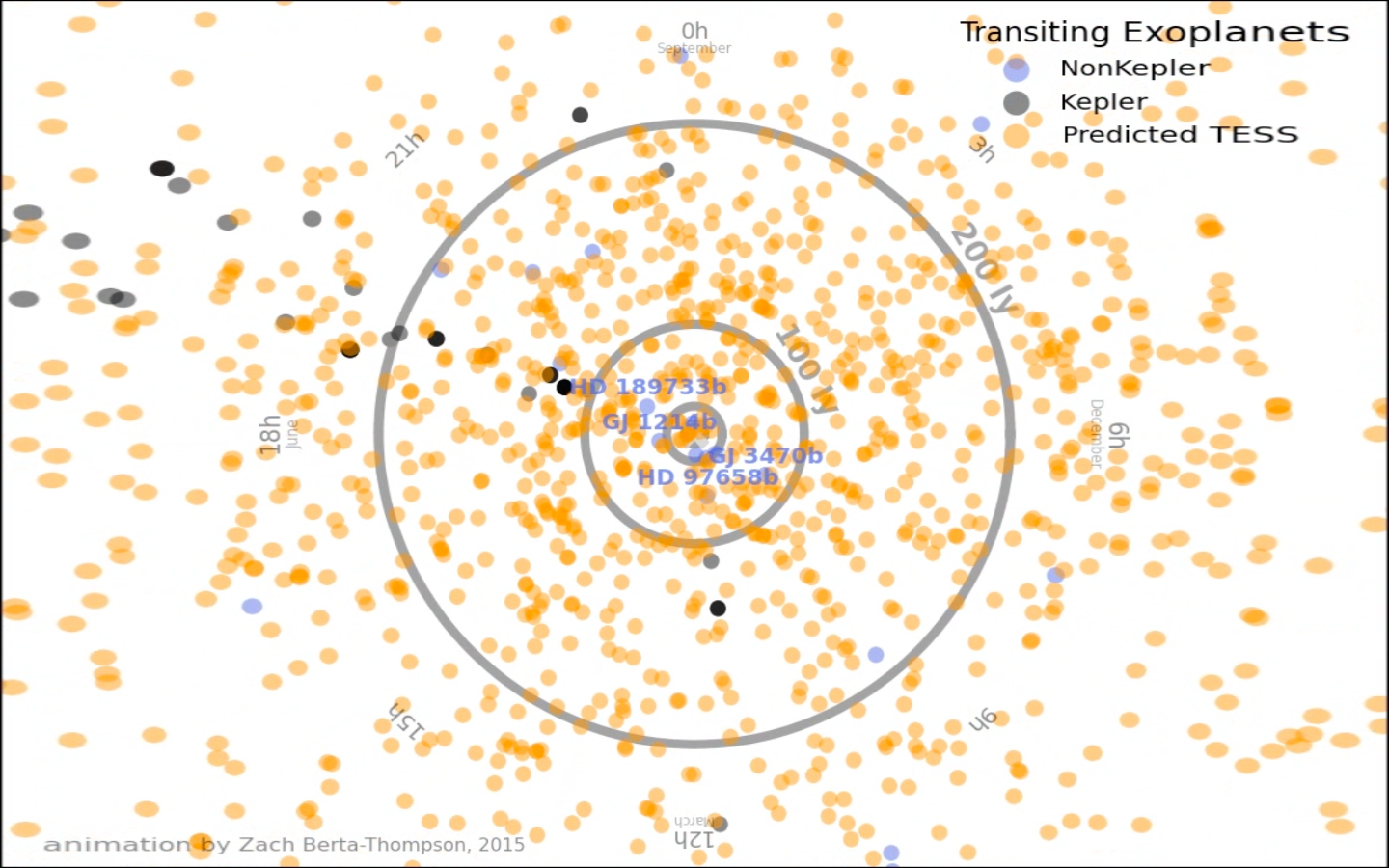

The last talk of the session was from George Ricker, the PI of the TESS mission, the follow-up mission to Kepler, about TESS’s status and prospects. Apparently, the mission will observe more than 2 million stars! Orbiting many of those stars will be nearby habitable planets, and Ricker showed an amazing simulation of where those stars might be found (courtesy of Zach Berta-Thompson of UC Boulder), a still from which is shown below.

I’m at the beautiful Gaylord Convention Center in Grapevine TX, attending the 229th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

I’m at the beautiful Gaylord Convention Center in Grapevine TX, attending the 229th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Today’s the first day, and it will be chockfull of presentations, posters, and press releases.

Given my research focus on exoplanets, I’ll mostly be attending talks on that topic, but I’m going to duck out at one point to hear about the solar eclipse, coming up in August this year.

Fortunately for me this year, my presentation was scheduled on the first day of the meeting, in the first session of contributed talks. That means I’ll be able to focus on the rest of the meeting without being preoccupied by preparing for my own presentation. I’ve posted my slides below.

Stay tuned this week for more.