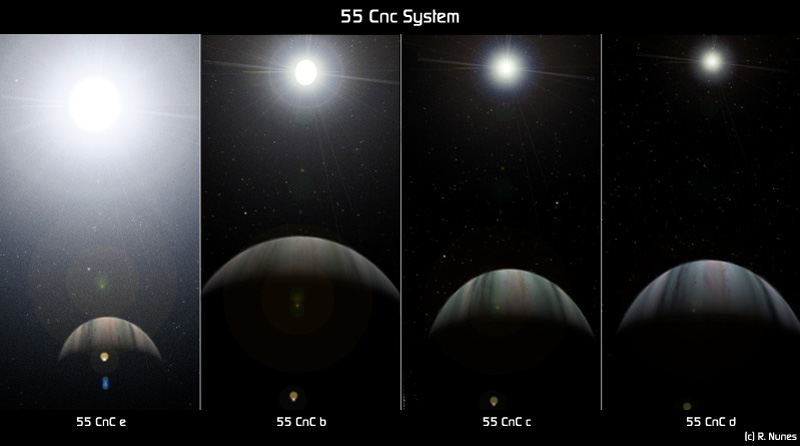

There are currently only about half a dozen Earth-sized planets orbiting stars that you can see without a telescope or binoculars, called “naked eye stars“. Among this select class, the 55 Cancri system stands out as unique – located in the constellation Cancer, 55 Cancri, a star very similar to our Sun, hosts five planets, ranging from Earth-sized to bigger than Jupiter.

Artist’s conception of the views from four of the 55 Cancri planets. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:55cnc.jpg.

The innermost planet, 55 Cancri e, is the one most similar to our own planet, with a mass eight times Earth’s and radius twice Earth’s.

In some big ways, though, 55 e is a far cry from Earth – it’s almost a hundred times closer to its star than we are to ours, meaning its year is only about 18 hours long. Recent observations from the Hubble Space Telescope also suggest it has a hydrogen and helium atmosphere with a pressure comparable to Earth’s. But one thing 55 e might have in common with Earth: active volcanoes.

A recent study from Patrick Tamburo of Boston University analyzed infrared observations of the 55 Cancri system collected by the Spitzer Space Telescope and found evidence for some sort of dramatic change on 55 e.

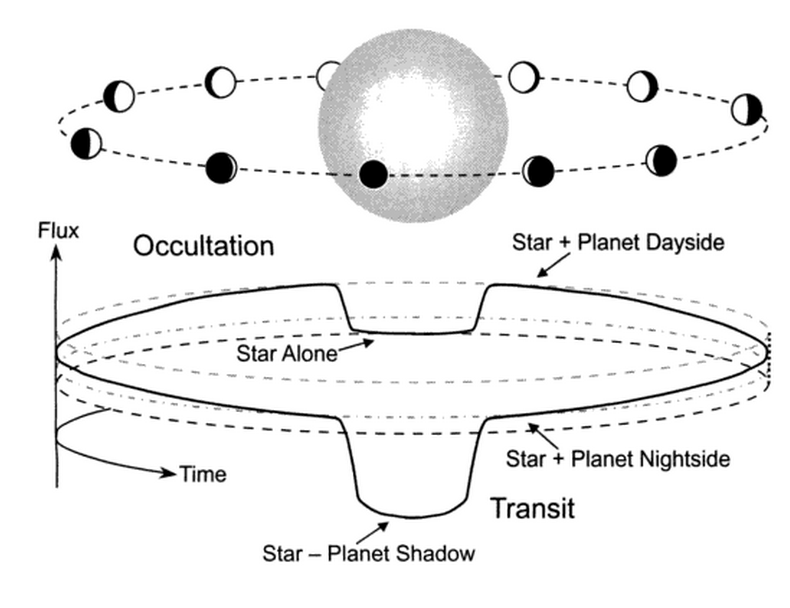

The observations were collected just as 55 e plunged behind the star as seen from the Earth. Such a configuration is referred to as a planetary eclipse or occulation.

A comparison between transits and secondary eclipses (also sometimes called occultations). In a planetary transit, the planet crosses in front of the star (see lower dip) blocking a fraction of the star’s brightness. In a secondary eclipse, the planet crosses behind the star, blocking the planet’s brightness (see dip in the middle). The latter dip in brightness is fainter due to the faintness of the planet. Image credit: Josh Winn.

During an eclipse, the planet’s host star blocks out any light coming from the planet, which can produce a tiny dip in the total amount of light coming from the system.

The depth of that eclipse dip tells us how bright the dayside of the planet is – a very bright dayside would produce a big dip, indicating a hot and bright atmosphere, while a dark dayside would produce no dip, meaning a very cool atmosphere. But what if the dip is shallow during some eclipses and deep during others?

That’s exactly what Tamburo and colleagues found. In 2012, the planet exhibited eclipses with little to no depth. But when Spitzer revisited the system in 2013, it found whopping eclipses, with the planet emitting about 0.02% of the star’s light. This change corresponds to an increase in the planet’s apparent temperature of more than 1,000 degrees Kelvin (about 2,000 F).

What could cause such a dramatic change? As in the original study of these data, Tamburo and colleagues explore the possibility that an enormous volcanic eruption on 55 e could have injected dust high into the atmosphere (about 100 km up) in 2012, shrouding the lower and hotter atmosphere and surface. By 2013, the dust cloud could have settled out, raising the planet’s apparent temperature.

How plausible is this idea? Surprisingly, plausible actually. Previous studies of 55 e have shown that interactions between the planet and its sibling planets could induce enormous amounts of tidal heating within 55 e, similar to Jupiter’s moon Io, and potentially powering tremendous geophysical activity.

Large terrestrial eruptive plumes have reached 40 km height in Earth’s atmosphere, so perhaps such altitudes are not unreasonable on 55 e. However, 55 e has a surface gravity more than twice Earth’s and its atmospheric temperatures are likely much higher than Earth’s, both of which would inhibit ascent of a volcanic plume. So it’s not totally clear this exciting idea could pan out in detail.

In any case, these new results may represent the emergence a new field of study, observational exoplanetary volcanology, and maybe scientists a few generations from now will be trying to predict volcanic activity on Kilauea and Cancer.