For Boise State Physics’ First Friday Astronomy event in January, we will host Leif Edmondson, president of the Boise Astronomical Society. Edmondson will talk about ancient Babylonian astronomy, so for this month’s blog post, rather than steal his thunder, I decided to talk about an astronomical tradition disconnected from Babylon: ancient Korean astronomy.

Korean astronomy goes back thousands of years and, aside from China, Korea has the longest history of astronomy in the world. Korea also hosts the oldest known astronomical observatory in east Asia, built by one of the earliest queens of the ancient world. And even today, Korean astronomers continue to innovate and discover, building on this deep past.

Heavenly Disapprobation

As for many cultures, the beginnings of Korean astronomy have faded into the mists of the past, but some of the oldest astronomically-relevant structures in Korea date back to at least 3000 BC. Large stone grave sites, called dolmens, dot the Korean peninsula and exhibit carvings identified as constellations. The Adeukgi dolmen displays features corresponding to the Big Dipper.

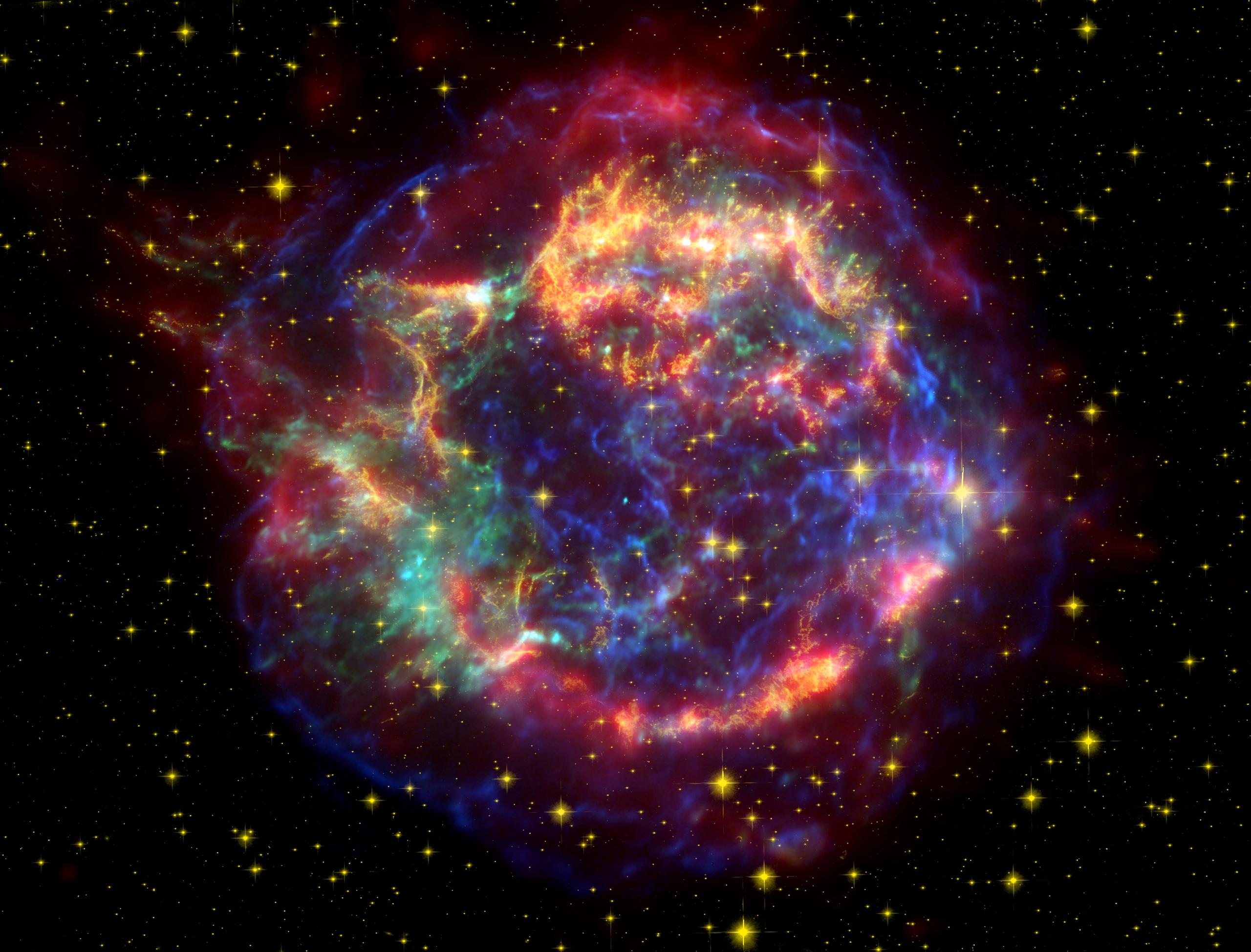

Cultural transmission throughout east Asia brought Chinese traditions to Korea, and as many east Asian cultures, Koreans adopted Chinese cosmology, by at least the 7th century AD. According to that tradition, features and motions in the night sky betokened heavenly opinion on the ruling administration. The regular, seasonal progression of celestial events indicated approval, while dramatic and unexpected apparitions of comets and supernovae spelled disapprobation and doom. Korean astronomers recorded supernovae in 1054, 1572, and 1604 AD, which correspond to supernova later identified as the Crab Nebula, B Cassiopeiae, and Kepler’s Supernova, respectively.

Those supernovae were also recorded by Chinese, Japanese, Islamic, and European astronomers. However, ancient Korean logs record a similar “guest star” in 1592 in the constellation Cassiopeia which does NOT seem to have corresponding records from other cultures. Cassiopeia does, indeed, host the remnants of a supernova, Cassiopeia A, but astronomical estimates suggest light from that supernova would only have reached Earth in the 1660s. Astronomical historians have speculated that, perhaps, this guest star was a supernova imposter, the poorly understood precursor to a supernova. Whether such a nova was actually observed remains unclear, but in a dark coincidence, Japan’s bloody Imjin War invasion of Korea began in 1592.

Queen Sonduk and the Star Tower

During Korea’s Three Kingdom’s era, the Kingdom of Silla was ruled by Queen Sonduk, the first female monarch in Korea. Queen Sonduk was born around AD 610 to the king of Silla, Jinpyeong. Sonduk was apparently a precocious child. Upon receiving a painting of peonies from the Chinese court, seven year old Sonduk correctly inferred that the flowers must have no smell. “[Otherwise] there would be butterflies and bees around the flowers in the painting.”

King Jinpyeong had no male heirs, and so Sonduk became Silla’s ruler in AD 632, which resulted in rebellion among Koreans who objected to a female ruler. In part to allay such objections, Queen Sonduk implemented widespread social welfare programs and temporary tax exemptions for farmers. She also promoted the useful arts and indulged her own passion for astronomy by commissioning construction of an astronomical observatory, Cheomseongdae, which was completed in AD 647. Cheomseongdae, whose name means “star-gazing tower”, can still be visited in southeastern South Korea, making it the oldest astronomical observatory in Asia and perhaps in the world.

Modern Korean Astronomy

Today, Korea continues its long astronomical tradition under the auspices of KASI, the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute. KASI supports a wide variety of astronomical research and international partnerships, including the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) consortium. KASI has also developed specialities in radio and optical astronomy.

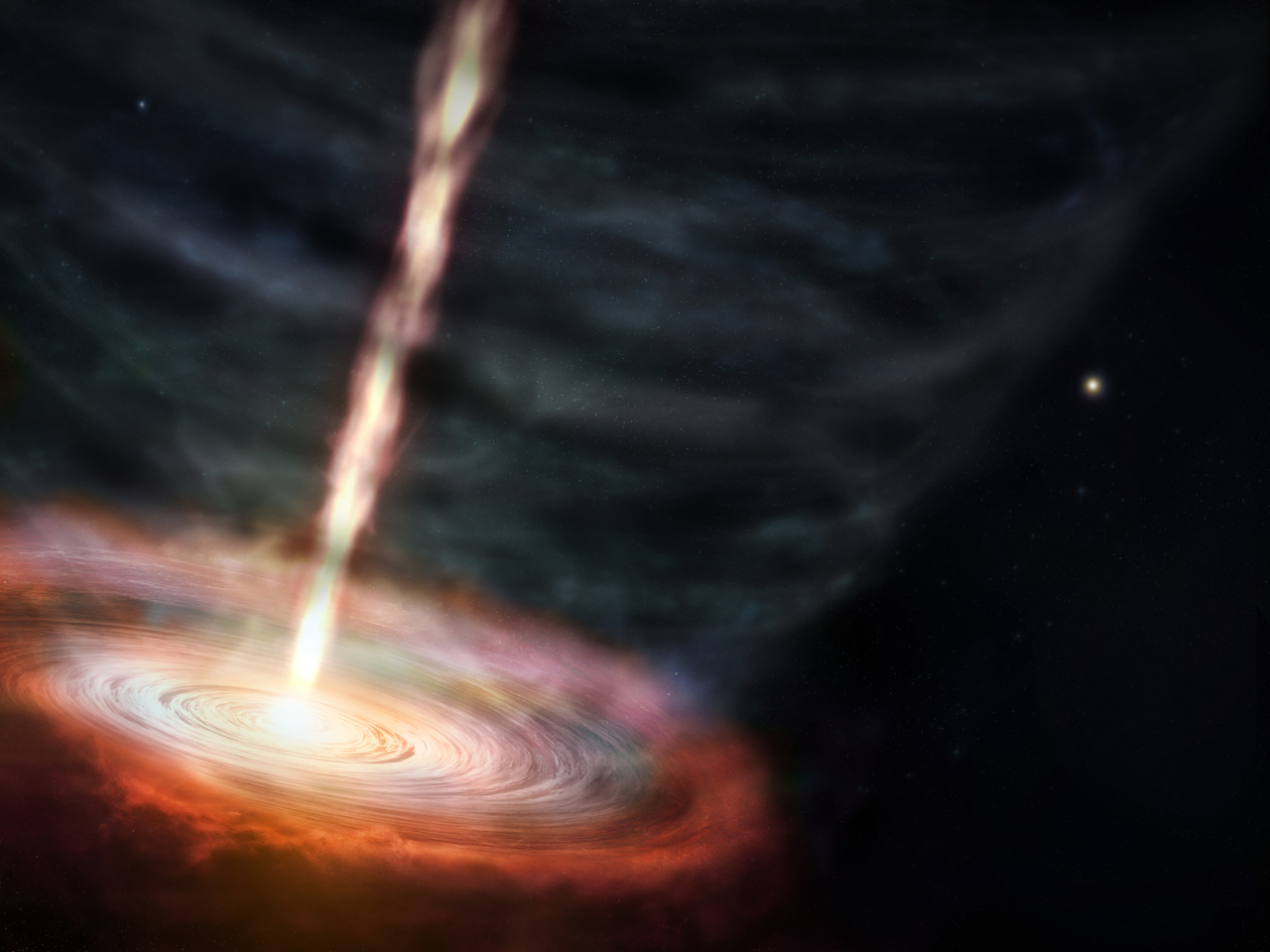

For instance, KASI operates the Korean VLBI Network, KVN, a very long baseline interferometry network operating at millimeter wavelengths. These radio telescopes are spaced hundreds of kilometers apart, producing an effective spatial resolution equivalent to that of a 500-km radio telescope, which allows astronomers to very precisely resolve radio objects in the sky — the array can resolve features as small as a few millionths of a degree.

True to their astronomical tradition, Korean astronomers use the KVN array to study the formation and death of stars. For instance, the KVN has mapped star-forming regions using laser emission by molecular species such as water and methanol. These kinds of maps help astronomers understand the origins of stars and planetary systems like our own.

To learn more ancient astronomy, join Boise State Physics’ First Friday Astronomy event on Friday, Jan 5 to hear Boise Astronomical Society president Leif Edmondson discuss Babylonian astronomy. The presentation will be in-person on Boise State’s campus and streamed live via youtube at http://boi.st/astrobroncoslive.