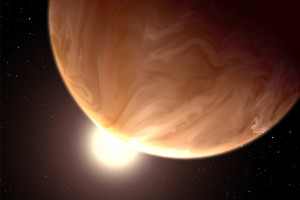

Artist’s conception of cloudy GJ 1214 b. From http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/07/science/space/the-forecast-on-gj-1214b-extremely-cloudy.html.

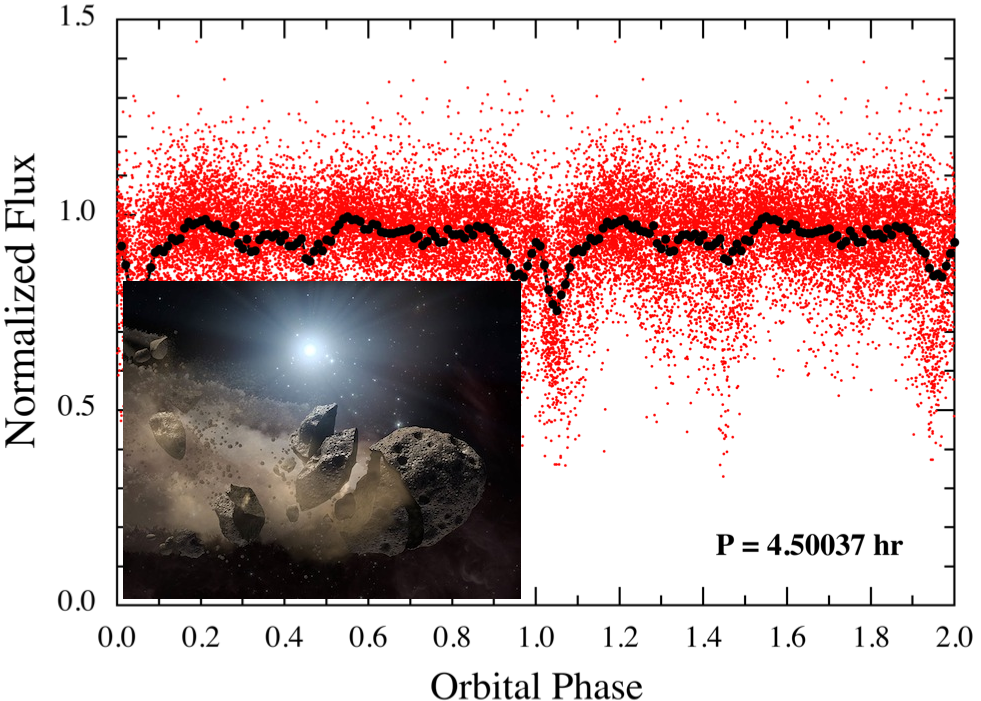

At journal club this week, we discussed the recent discovery using data from the K2 mission of the sub-Neptune planet K2-28.

This planet, roughly twice the size of Earth, circles a very small M-dwarf star so closely that it only takes two days to complete one orbit. Even though the planet is very close to its star, the star is so cool (3000 K) and so small (30% the size of our Sun) that the planet’s temperature is only 600 K. (A planet in a similar orbit around our Sun would be 1200 K.)

The authors of the discovery paper point out that this planet is similar in many ways to another famous planet, GJ 1214 b. Like GJ 1214 b, K2-28 b is member of this puzzling but ubiquitous class of sub-Neptune planets — planets that fall somewhere between the Earth and Neptune in size and composition and do not exist in our solar system*. Both planets also orbit relatively nearby M-dwarfs, which means, like GJ 1214 b, K2-28 b might be amenable to follow-up observations.

Previous follow-up observations of GJ 1214 b indicated that planet’s atmosphere is very cloudy or hazy. So K2-28 b could provide another very important toehold along the road toward understanding this strange class of hybrid planet.

*unless Planet Nine turns out to be real