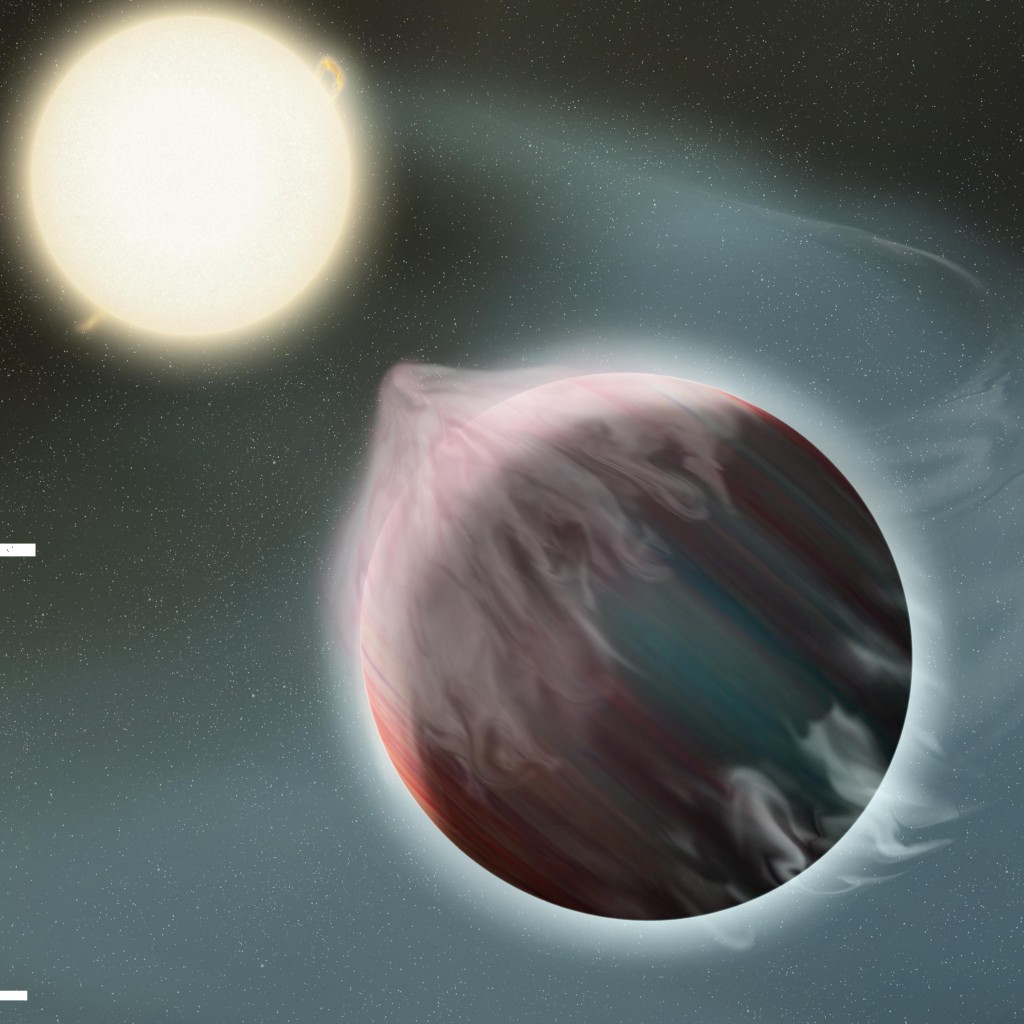

Some planets in other solar systems orbit so close to their stars that they are spiral inward, ultimately to be ripped apart and eaten by their stars.

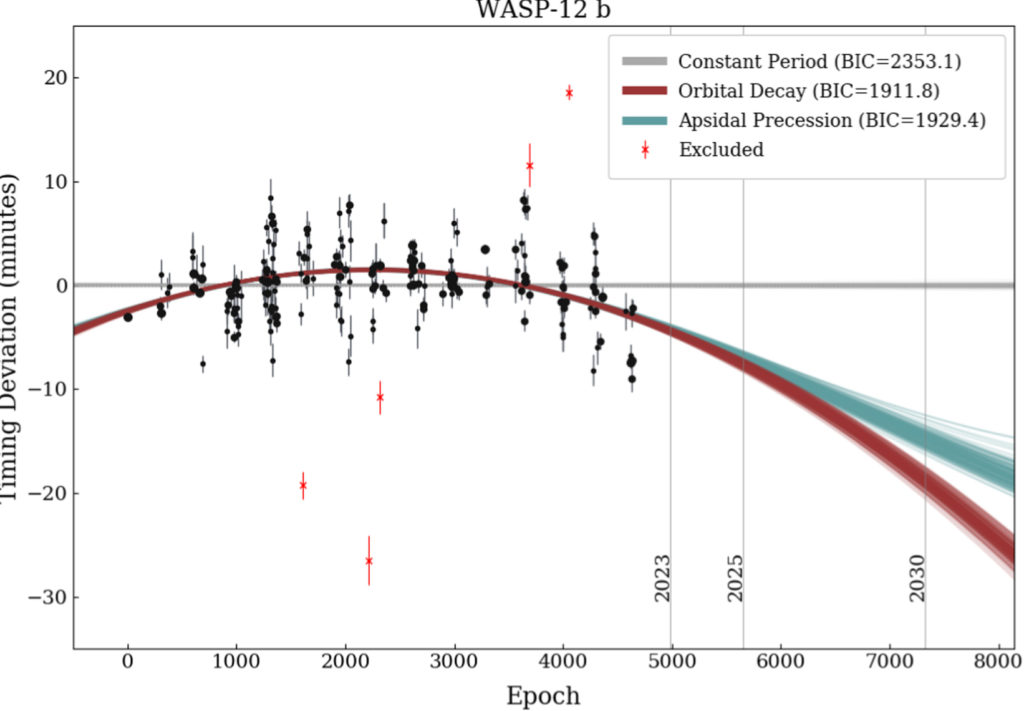

Looking for signs of that in-spiral, many astronomers, including students in my own research group, study transit signals — the shadows of planets as they pass in front of their host stars, as seen from Earth. For a planet spiral into its star, the time between one transit and the next will get shorter and shorter over many years. And so by measuring many transits, we can find signs of tidal in-spiral.

One big problem with looking for such tidally-driven signals is that other effects can also effect the time between transits, and so we need a good way to distinguish between these different effects.

In a recent paper from our group, we map out some ways to tell the difference between these different effects using tides. The bottom line: it’s not easy to tell the difference, but observations of exoplanet transits by citizen scientists can be a really important tool for the long-term monitoring required to find tidally decaying worlds that are not long for this world.

Related Publications

- “Metrics for Optimizing Searches for Orbital Precession and Tidal Decay via Transit Timing and Occultation Timing.” (2026). The Astronomical Journal, Volume 171, Number 2.

- “Doomed Worlds. I. No New Evidence for Orbital Decay in a Long-term Survey of 43 Ultrahot Jupiters.” (2024). The Planetary Science Journal, Volume 5, Number 7.

- “Metrics for Optimizing Searches for Tidally Decaying Exoplanets.” (2023). The Astronomical Journal, Volume 166, Number 4.