Asking questions at a scientific conference is one of the most exciting but intimidating aspects of conference attendance. Here, I give a few suggestions (write down your questions, introduce yourself, etc.) to ease the process.

Annual scientific conferences are one of the highlights of working in astronomy – you get to visit a new place, you get to meet with old friends, and you get to hear about scientific results so cutting-edge they can change from hour to hour. Optimizing the conference experience requires a fair amount of planning, but fortunately, there are a number of online guides explaining how to plan your conference, how to prepare an oral presentation, how to make a poster, etc.

At the end of most presentations, the audience is invited to ask questions, and these question-and-answer sessions can lead to some of the most exciting, interesting, and dramatic developments at a conference. These exchanges can also be very important forums for feedback and can give a budding scientist a chance to make connections to the broader community.

But asking a question in front of a big crowd can be a little daunting, and unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be any advice online about how to do it. (UPDATE: After writing this blog post, I found this discussion that echoes some of my points.)

So I thought it would be helpful to collect a few thoughts on the topic. These ideas are by no means exhaustive and may not be widely agreed upon, so if anyone has suggestions, please don’t hesitate to let me know.

Here we go:

1. Don’t feel bad for feeling nervous – One of my colleagues once told me she felt so nervous walking up to the mic to ask questions that she thought her voice would crack. That made me feel a lot better about my own intestinal lepidoptera. Most people get anxious when speaking in front of hundreds of the smartest people in the world, so don’t stress about feeling that way.

If you anticipate wanting to ask a question, though, you can sit close to the mic at the beginning of the presentation to shorten the walk.

2. Write down your question – I tend to take short notes during presentations, usually about things to ask the speaker after the presentation or even in an e-mail after the conference. But it’s very helpful to already know what you want to say before getting to the mic, so not a bad idea to write it down.

3. Introduce yourself – Several times after one of my presentations, someone has asked an interesting question or made a good point that I wanted to follow up on afterward. However, after asking their question, the person melted back into the crowd to remain anonymous forever. So it’s very helpful if you give your name and affiliation before asking your question. Keep in mind that the speaker may be staring into bright lights and not able to see the audience.

I also think it’s just common courtesy to introduce yourself, and if, as a community, we encourage questioners not to remain anonymous, we will reduce the temptation to attack the speaker.

4. Keep it short, and don’t get hung up on a minor point – A good anecdote from this website shows what I mean here: “I … gave my talk and the Q&A followed, then a questioner began a diatribe that lasted at least 20 minutes: in fact, it was a mini-lecture. At first I thought I heard a question begin to emerge, but it disappeared – after that the ‘lecture’ was in full flow. … Finally the chair [of the session] rose to stop him by thanking him and saying it was halfway through lunch, to much relief.”

If you have a lot to say or would like to address a very narrow, technical point in the presentation, it’s probably best to wait until after the session to talk to the speaker. Remember that the presenter is not the only person to whom you are speaking. I think it’s best to focus on questions of general interest, not just to the one or two people who specialize in, for instance, tidal dissipation parameters. Of course, this is a scientific conference where the audience is full of specialists, so there’s a balance to strike here.

Also, at most conferences, there are only a few minutes for questions, so keeping your question short leaves time for others.

5. Don’t ambush the speaker – Once, early in my grad career, a very preeminent astronomer introduced himself at breakfast and expressed a big concern about some recent work I’d done. It was a very good point, and, at the time, I said I didn’t have an answer but would get back to him. After I gave my talk later that afternoon, this astronomer raised the same question, publicly suggesting to hundreds of others that my results were probably wrong. Of course, I still didn’t have an answer for him. (As it turned out, he was wrong, and we responded to those concerns in a few subsequent papers.)

The point of the story is not to complain but to say that it’s not helpful to attack a speaker publicly since it can be hard for someone to come up with a thoughtful response on the spot. I think it’s much more effective (and more polite) to raise such concerns privately (at least at first), perhaps one-on-one or via e-mail. Then, if the presenter refuses to respond or obfuscates, maybe it makes sense to raise your concerns in a public forum so the community is aware of the problem.

6. When in doubt, save it for the post-session – In the end, you almost always have a chance to talk with the speaker later. So if you’re hesitant to ask during the question session, approach the speaker afterward.

It’s true that there are some jerks in the scientific community, but the vast majority of scientists I’ve met are considerate and thoughtful. And even most jerks love it when someone has taken enough interest in their work to ask questions.

If you’re uncomfortable approaching someone you don’t know, reach out to your colleagues at the conference to see if anyone knows the speaker. And then, of course, e-mailing the question is always possible. Another good reason to write it down.

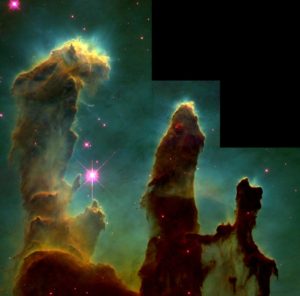

What do “bubbles” and “yellowballs” have to do with star formation? Identified in mid-infrared Galactic plane surveys, these objects are both named for their appearance in infrared wavelengths.

What do “bubbles” and “yellowballs” have to do with star formation? Identified in mid-infrared Galactic plane surveys, these objects are both named for their appearance in infrared wavelengths.