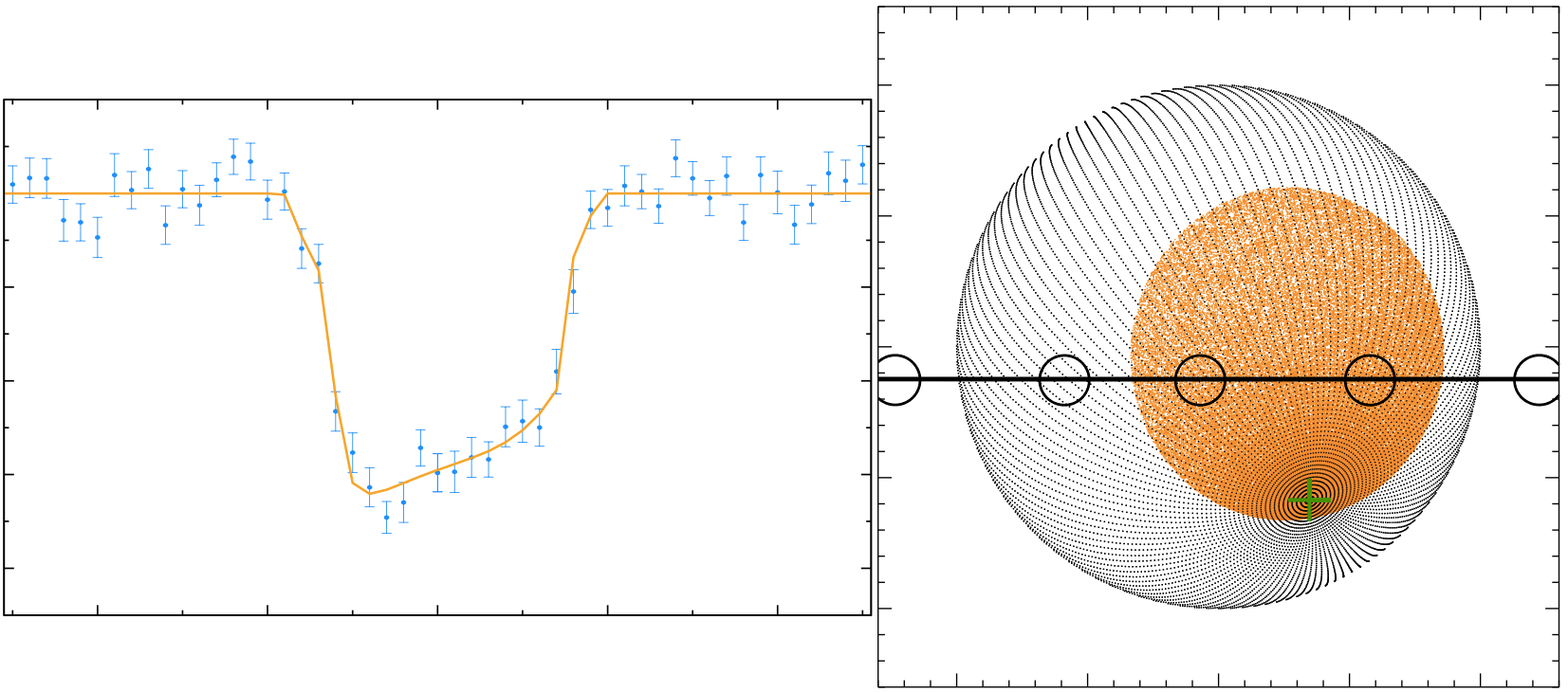

CoRoT-7 b was the first confirmed rocky exoplanet and was discovered by the CoRoT mission, but, with an orbital from its host star of only 0.0172 AU (100 times closer than the Earth is to the Sun), its origins may be unlike any rocky planet in our Solar system. In Jackson+ (2010), my colleagues and I considered the roles of tidal evolution and atmospheric mass loss in CoRoT-7 b’s history, which together have modified the planet’s mass and orbit. If CoRoT-7 b has always been a rocky body, evaporation may have driven off almost half its original mass, but the mass loss may depend sensitively on the extent of tidal decay of its orbit. As tides caused CoRoT-7 b’s orbit to decay, they brought the planet closer to its host star, thereby enhancing the mass loss rate. Such a large mass loss also suggests the possibility that CoRoT-7 b began as a gas giant planet and had its original atmosphere completely evaporated. In this case, we found that CoRoT-7 b’s original mass probably did not exceed 200 Earth masses (about two-third of a Jupiter mass). Tides raised on the host star by the planet may have significantly reduced the orbital semimajor axis, perhaps causing the planet to migrate through mean-motion resonances with the other planet in the system, CoRoT-7 c. The coupling between tidal evolution and mass loss may be important not only for CoRoT-7 b but also for other close-in exoplanets, and future studies of mass loss and orbital evolution may provide insight into the origin and fate of close-in planets, both rocky and gaseous.

Related Press:

Related Scientific Publications:

- Jackson+ (2010). “The roles of tidal evolution and evaporative mass loss in the origin of CoRoT-7 b.” MNRAS 407, 910.

- Jackson+ (2010). “Is CoRoT-7 B the Remnant Core of an Evaporated Gas Giant?” BAAS 42, 444.