Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, was discovered by the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens in 1655, the same year courts in Virginia first ruled slavery was legal in the American colonies. It took another 350 years before humans visited Titan upclose, leaving this, the largest moon in the Solar System, an object of wonder and speculation. But even after many years of intimate study, Titan remains enshrouded, both figuratively and literally. Its secrets may persist until NASA’s Dragonfly mission visits the world again in 2034, and if history is any guide, probably long after too.

We Never Thought Titan Storms Could Be

Before the Cassini-Huygens mission, the most detailed and close-up views we had of Titan came from the Voyager 2 flyby of the Saturn system in 1981, the same year the song “Believe It or Not” topped the Billboard charts. Voyager 2 sped through the Saturn system, essentially taking only quick snapshots of each object. Scientists found that Titan’s atmosphere was thick with organic haze, and so the best images we got of Titan only showed a smoggy, orange ball. The surface remained completely obscured.

But even though Titan’s surface was unknown, scientists were still able to learn a lot from Voyager. They found that Titan’s atmosphere is made mostly of nitrogen – like Earth – but with a lot of methane and ethane thrown in – unlike Earth. Temperatures near the surface were -290 degrees Fahrenheit, cold enough that these organic molecules could be liquid, raising the possibility that Titan could have lakes or even oceans of liquid natural gas.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, scientists spent a lot of telescope time trying to peer through Titan’s haze. However, because Titan is so far from Earth, it appeared only as a blurry dot, almost impossible to resolve across more than a billion km. Even so, scientists analyzed its infrared spectrum and found strange variations in the spectra taking place over just a few days. By performing radiative transfer calculations, scientists deduced that the spectral variations were caused by the appearance and disappearance of near-surface storm clouds.

So even though it receives less than 1% of the storm-powering sunlight Earth gets, Titan still had active weather. But what kind of weather could a frigid, icy world in the outskirts of the solar system have?

Mapping A World Away

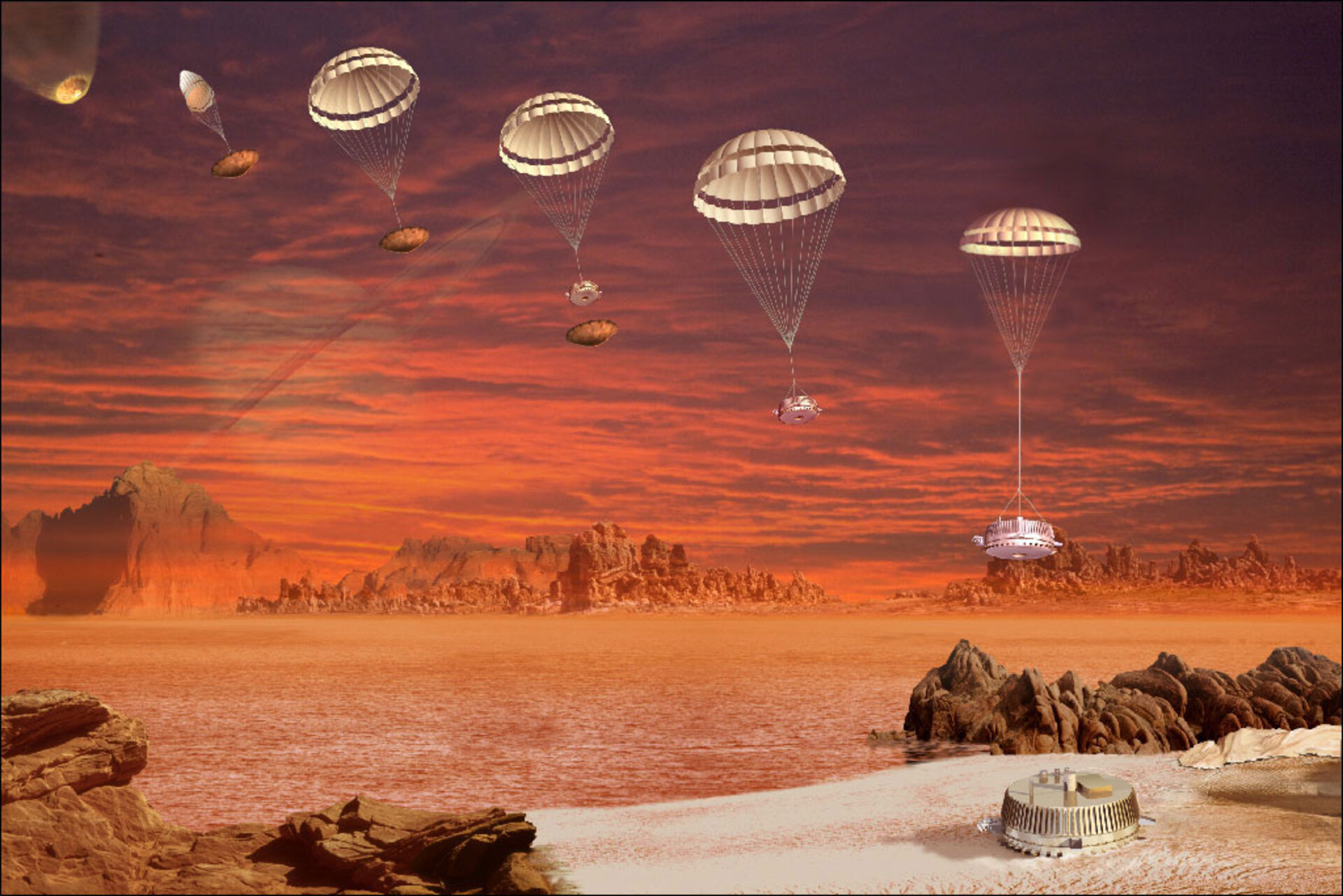

NASA launched Cassini-Huygens Mission in 1997, the same year Chumbawamba released “Tubthumping”. In partnership with the European Space Agency, NASA’s Cassini-Huygens mission was designed to orbit Saturn to explore the system in much more detail than the Voyagers. The mission included the Huygens lander, designed to probe the atmosphere of Titan directly. When Cassini-Huygens arrived in the Saturn system in 2004, Huygens detached from the Cassini spacecraft and fell toward Titan. Huygens then descended on a parachute, sniffing Titan’s atmosphere and returning images of the world’s previously unmapped surface.

The world unveiled by Huygens was strangely reminiscent of Earth. Huygens saw craggy mountains, steep valleys, and large river outwashes. As Huygens landed on Titan’s surface, the warmth from the spacecraft evaporated liquid methane in the gravelly surface, releasing a puff of methane gas that registered in Huygens’ sensors. Apparently, the surface was recently wetted by a methane storm.

Combining these data with data collected over many years by the Cassini spacecraft, scientists developed a complex and detailed picture of Titan and its climate. Like the American Southwest, Titan is a world of extreme weather – methane/ethane rain, concentrated near the poles, falls only very occasionally. But, when it does fall, the rain comes in flash floods. These violent torrents erode the surface, carving deep river channels, and collect in vast polar seas.

The same climatic processes that wet the Titanian poles also dry the equator, making it as arid as a desert. In fact, Cassini discovered sprawling dune fields encircling Titan’s equator. But, remember, the surface of Titan is made not of rock but of rock-solid water ice, and Titan’s dunes are not made of rocky sands, like on Earth, but some complex and as yet mysterious organic molecules.

NASA’s Glad Hype

There are a lot of organic molecules on Titan, so what about prospects for life there? Certainly, the world is too cold for life as we know it – Titan’s surface water remains almost completely frozen. But occasionally, comets crash into Titan’s surface, making large craters full of melted water. Toss in some of the organic haze molecules constantly raining down from the atmosphere and, baby, you’ve got a stew going. Could life get a toehold in such an environment?

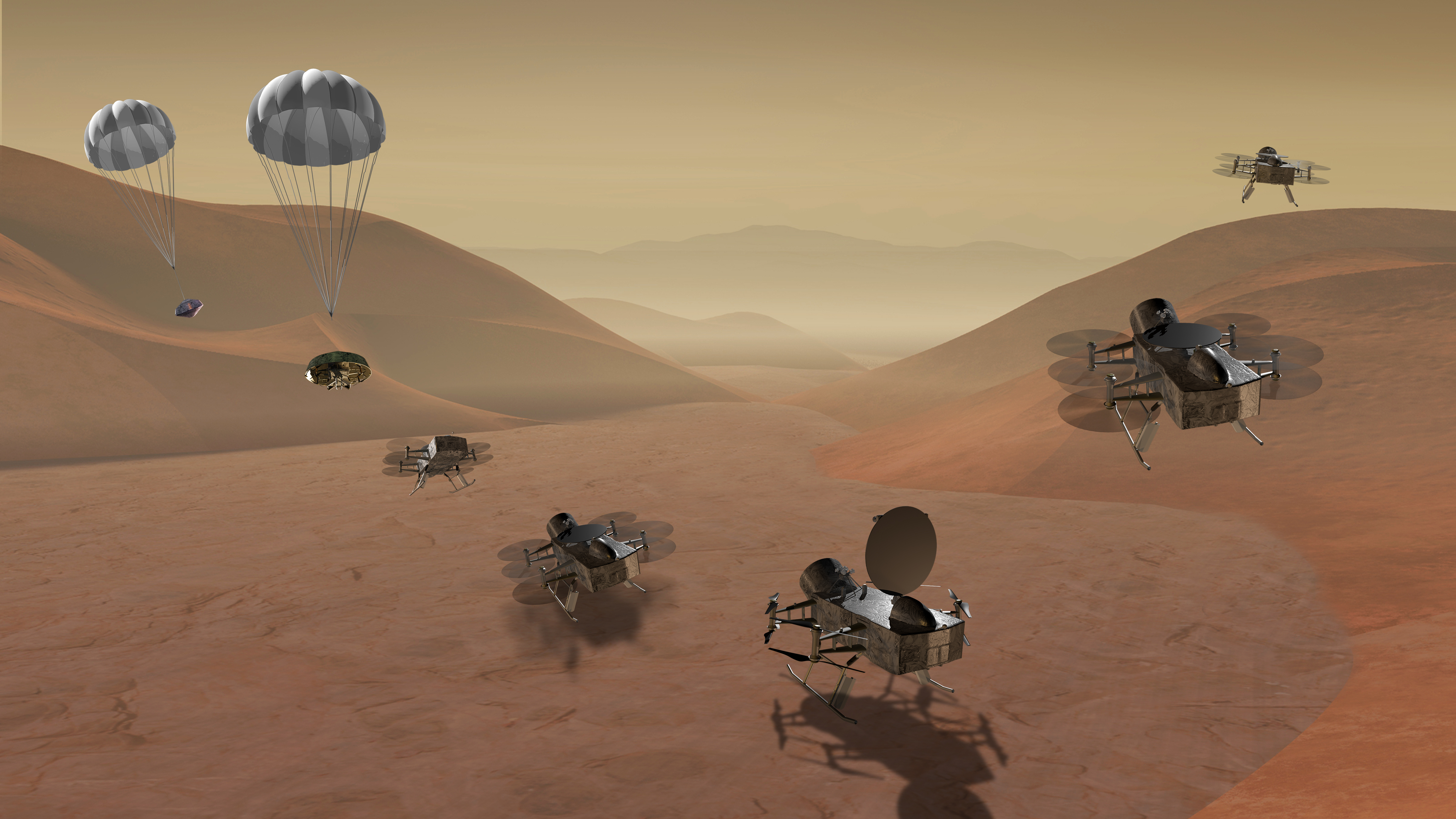

In June 2019, NASA selected the Dragonfly Mission to explore that exact question. Dragonfly is NASA’s first airborne science mission, a multicopter designed to hop from one dune to another. It will explore near the Selk impact crater, a place where liquid water and organics probably mixed together to perhaps form the precursors of life. Dragonfly is scheduled for launch in 2027 and arrival on Titan in 2034.

Want to learn more about Titan? Join Boise State Physics for our First Friday Astronomy event on Fri, Dec 1 at 7:30p MT on-campus and online (http://boi.st/astrobroncoslive) to hear Prof. Juan Lora of Yale discuss “Titan’s Methane Weather, Climate and Hydrologic Cycle”. The event is open to the public and donation-supported.