Professional astronomers spend a lot of time on reading other astronomers’ research to learn what’s going on in the field and to incorporate new, best results into their work.

Traditionally, that research is officially presented to the astronomical community in the form of a peer-reviewed article printed (or at least hosted) in a professional astronomical journal, such as “The Astrophysical Journal“, “The Astronomical Journal“, or the venerable “Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society“.

However, scientific research articles are very unlike newspaper or magazine articles — they don’t usually employ a narrative structure, and they include confusing words and references. Consequently, it can be hard for people new to the field to read and understand them.

So in response to insightful requests from my students, here’s a short primer about how to read astronomical research articles. A lot of this information probably applies to all scientific articles, but there are also some aspects unique to astronomical articles. If you have suggestions to improve this post, don’t hesitate to contact me.

How to Access Scientific Articles

There are lots of services to find astronomical articles, but the vast majority of astronomers use NASA’s Astrophysics Data System service to find articles. That service provides links to articles hosted on official journals’ websites (which may require a subscription to access) and (if they are available) to free versions on the open-access pre-print server astro-ph (which is part of the arxiv.org service).

Most journals allow the article authors to send out free versions of the published articles to anyone who requests them. So if you can work up the nerve (and most astronomers are very nice people or at least eager to have others read their work), e-mail the authors directly to politely request a copy. (Here’s a good article about how to e-mail scientists.)

Journals are the official repositories for the final versions of scientific articles. If an article appears in such a journal, it’s (probably) been through a review process (see below) and meets some basic standards of quality.

That doesn’t mean the results of an article are correct, and it’s not unusual for results in one article to be contradicted by subsequent articles (even subsequent articles from the same scientists). But with a published article, you can have some confidence in the results and process.

Many journals nowadays are managed by private companies, which must turn a profit. Consequently, subscriptions to some journals are very expensive, which severely limits public access to scientific research that has been supported by public tax dollars. (See stories like this one.)

This is why the astro-ph archive is a big deal – you can usually get free access to an article. One caution, though: ANYONE can post articles to astro-ph, and astro-ph articles have NOT necessarily been reviewed for accuracy by anyone.

How Articles are Written

The process of publication is, in many ways, arcane, confusing, and backwards, and scientists in many (but maybe not all) fields are working to improve it.

In a nutshell, a professional astronomer will spend several months, sometimes years, on a research project – running computer code, collecting observations, conducting experiments, etc.

At some point in the course of the project, the scientists will decide they have a self-contained, compelling story (knowing when to cut off a project and publish is almost more art than science). Then they will (if they haven’t already started) draft a scientific manuscript.

That manuscript usually includes

- Context and motivation for the project – What does recent, past work say about the problem? What questions remained unanswered?

- Technical aspects of their approach – What physical approximations were used in the code, and where might they fail? How long was each astronomical observation?

- Results from the project – What did the observations tell us about the planetary system?

- Summary of the conclusions and plans or suggestions for future work – How do the new results relate to the previous work? What observations should we collect next?

Eventually, the authors are satisfied with (or at least resigned to) the draft manuscript, at which point they submit to a journal.

The journal sends the article out to the other scientists (called “referees”) with relevant expertise for a (hopefully but not always) objective assessment of the work. There is usually some back-and-forth between the referees and authors (who are often kept anonymous to one another), with suggestions for improvements. Eventually, a final manuscript is “accepted for publication” and printed and/or posted online.

Reading Research Articles

Scientific articles can seem a little bit like a Gordian knot – convoluted and indecipherable. But the best way to read a scientific paper is to chop it into pieces, not to read the article from beginning to end like a short story. I’ll use a recent article from my own group as an example.

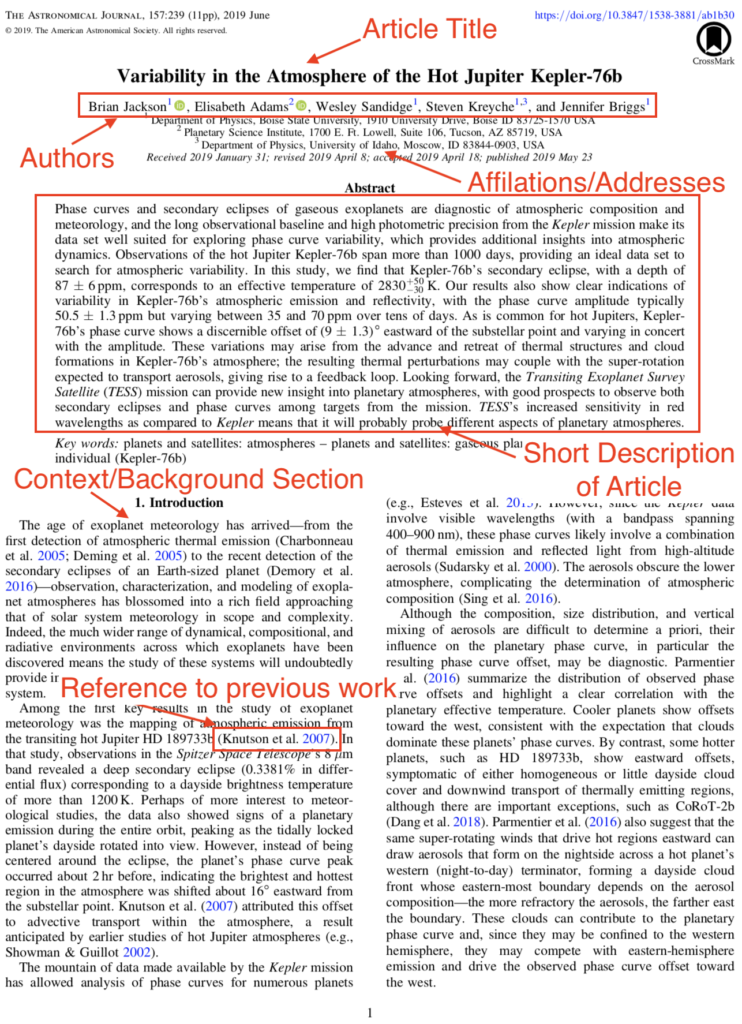

The image above shows the article’s first page. Different journals have different formats, but most will have the same information on the first page:

- Title of the article – (hopefully) tells you what the article is about

- Author list and affiliations – Who wrote the article, how can you get in touch with them. Usually, the person listed first (the “first author”) was in charge of the project and is the person you should contact if you have questions.

- Abstract – a short summary of article and main conclusions

- The introduction – Background and context for the project

Throughout the article, you will see references to previous work – for this article, those references look like “(Knutson et al. 2007)”. That means an article written by a group (“et al.“) led by someone named Knutson in 2007. In “The Astrophysical Journal”, the complete reference information is given at the end of the paper.

When I read a paper, I usually read the abstract carefully to get a clear sense for the paper’s about and what the authors conclude. Then I read the introduction if it’s pretty short (about a page). Longer than that, and I usually skim the introduction.

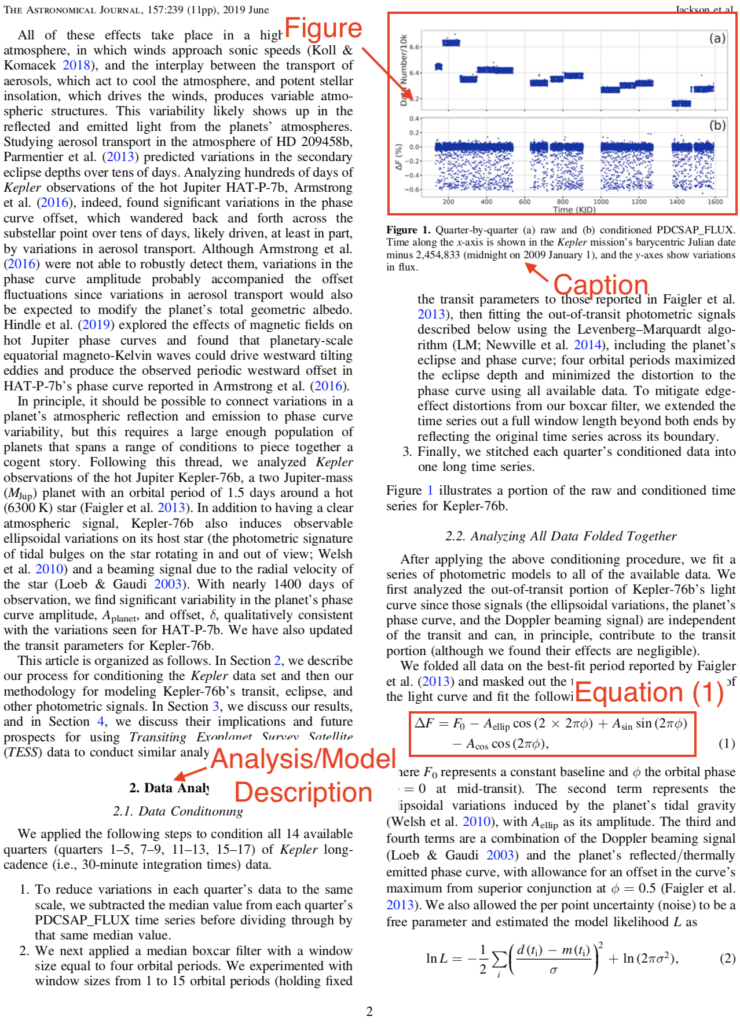

Usually the next section you see will be the technical description, which will include lots of figures and equations. I skip this section on my first read-through. It’s easy to get lost in the details, and if you’re not familiar with the techniques, this section will be undecipherable.

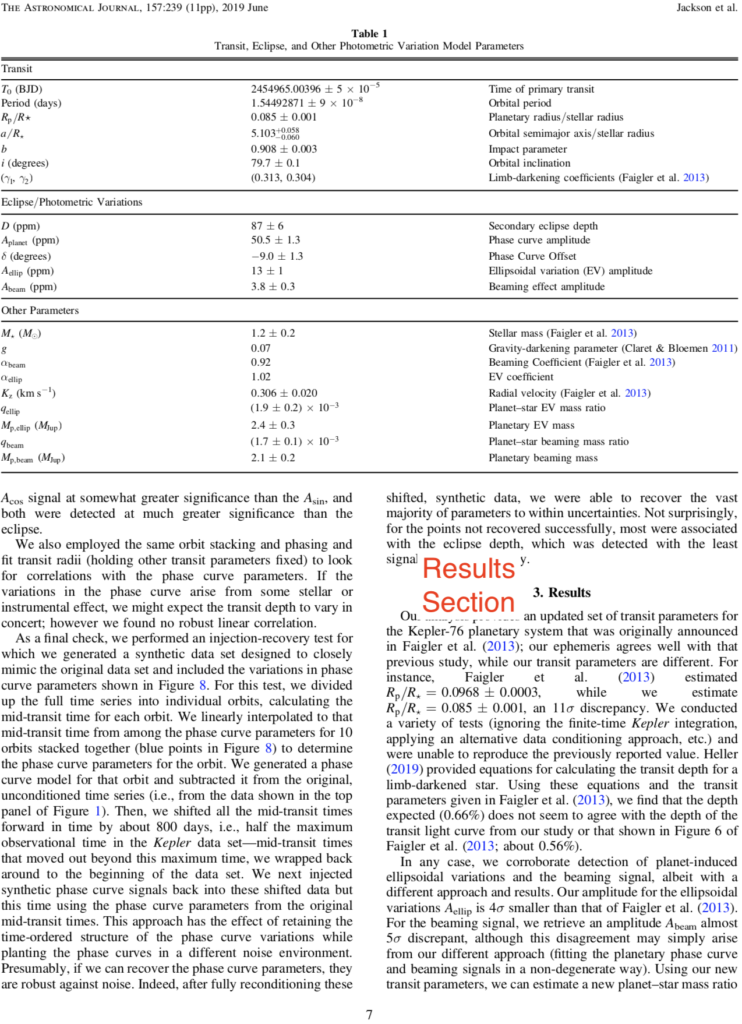

Then comes the results section. I will usually read this section if it’s short, with “short” meaning again one or two pages.

Finally, comes the conclusion and discussion. Though this is the last section of the paper, it’s usually the second section I read (after the abstract and/or introduction).

The last page of the article will usually include an Acknowledgments sections in which the authors will thank anyone who contributed to the article but is not listed as an author (including the anonymous referees who reviewed the paper).

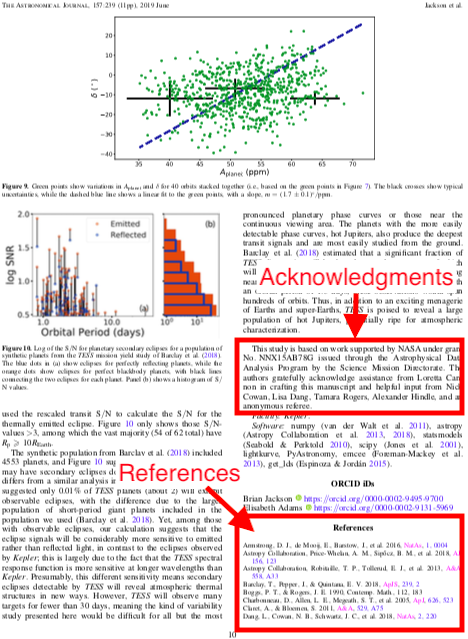

After that comes the references section, which provides the citation information for all the previous work referenced. Journals nowadays often use abbreviations that can be a little cryptic, so let’s look at the earlier example:

The figure above shows the reference information. We see the first three authors listed: Knutson, H.A, and then Charbonneau, D., and then Allen, L.E. The “et al.” means there were more contributing authors, but they are not listed to save space.

The “2007” means that was the year the article was published (but not necessarily the year the work was done), followed by “Natur”. In “The Astrophysical Journal”, “Natur” is short-hand for the journal “Nature“. Some journals don’t use such abbreviations, and others will have different abbreviations.

Finally, we see “447, 183”. These numbers usually refer to the volume and page number(s) in the journal where the article appears. Not all journals have volume or page numbers like this, so reference styles may vary.

All of this information is helpful if you want to find the referenced articles, which you can usually do through NASA ADS. In fact, usually all you need is the first author’s last name and the year the paper was published to find it, and ADS has a good guide about how to use the service to find articles.