Hosting a sub-surface ocean, Jupiter’s moon Europa is one of the most compelling targets for planetary exploration in the Solar System. Probing the moon’s geology, sub-surface ocean, and the possibility for life are the foci of NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission, set for launch in 2024.

While we wait for that mission, scientists keep chipping away at the Europan enigma using data from telescopic observations and from previous missions, particularly the Galileo mission. For example, Hubble observations suggest Europa has active geysers.

The Two Faces of Europa

One of the longest standing mysteries of Europa is the origin of its so-called hemispheric dichotomy. In short, as Europa revolves around Jupiter, it keeps one face always pointed toward the planet in a rotation state called “synchronous rotation”. (Earth’s own moon does the same thing.)

Ninety degrees to one side of the Jupiter-facing hemisphere is the leading hemisphere, the half of Europa that points in the direction of its orbital motion. The opposite side is the trailing hemisphere, which faces Europa’s past orbital location.

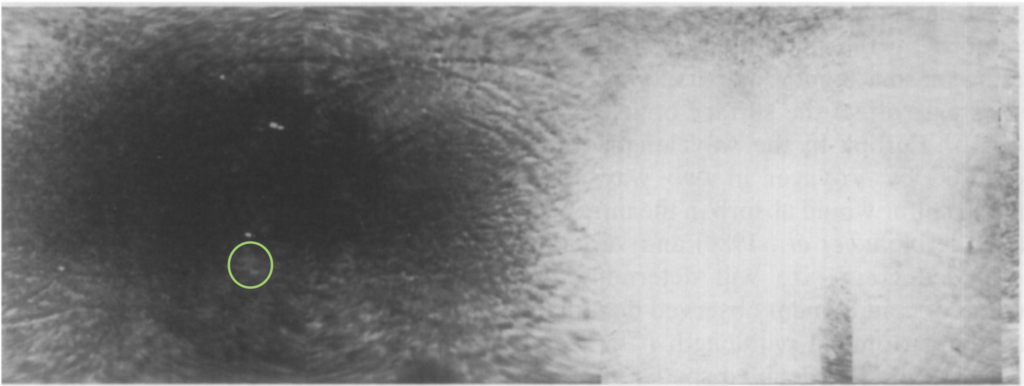

Perhaps counter-intuitively, Europa’s trailing hemisphere bears the fury of Jupiter’s magnetic field and radiation belts. Because Jupiter rotates so more quickly than Europa orbits (one rotation every 10 hours vs. 3.5 days for Europa’s orbit), charged solar wind particles trapped in the magnetic field are continually hurled at Europa’s trailing hemisphere. This constant sputtering chemically darkens the surface ice on the trailing hemisphere and likely explains the dichotomy.

This explanation makes one big assumption: that Europa has been tidally locked forever, or at least long enough that evidence for a different rotation state has been wiped away. Indeed, the rotation rate directly measured from Voyager and Galileo Missions images agrees completely is exactly what you’d expect for a tidally locked satellite.

But those constraints also allow for a tiny amount of non-synchronicity, perhaps allowing a reversal of the leading and trailing hemispheres every 6,000 years. That’s good because non-sychronous rotation seems to be required to explain one of the most dramatic geological formations on Europa.

Under (Tidal) Pressure

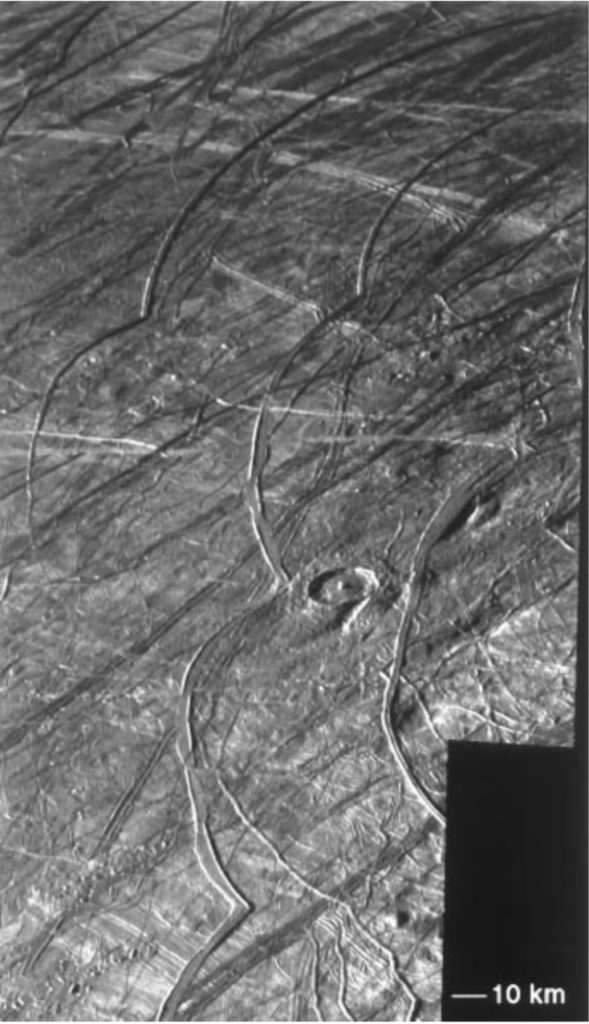

Geophysical scars mar Europa’s surface at almost all scales, from global to regional. The rifts and valleys that cross Europa, in many cases, arise from tidal stresses induced by Jupiter’s enormous gravity: as Europa circles Jupiter, the planet’s gravity stretches and compresses the satellite.

This tidal flexure can crack and rip Europa’s brittle icy shell, and the resulting rifts propagate across the surface in arcuate tracks that follow the maximum tidal stresses. In turn, the combination of Europa’s orbital motion and its rotation determine the path of maximum tidal stress across the surface.

Given that the tidal rifts form over the course of millennia, we can, in principle, use their shapes and orientations to infer Europa’s past rotation state. And analyses of the locations and orientations of cycloids implicate some non-synchronous rotation in Europa’s past.

In that case, then, we might expect the hemispheric dichotomy not to be so dichotomous — the darkening ought to extend a little ways across the boundary between the leading and trailing hemispheres. So does it?

Flummoxed by Fourier

The short answer seems to be “no”. A recent study by Burnett and Hayne of UC Boulder analyzed the contrast between the two hemispheres in ultra-violet and infrared wavelengths to enhance the contrast.

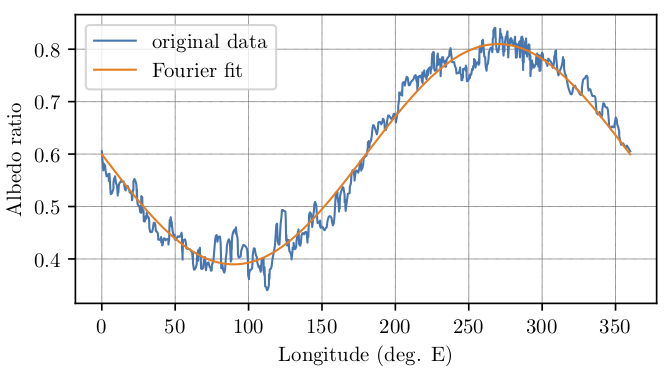

For their study, Burnett and Hayne used a technique called Fourier analysis. It turns that any oscillating pattern — electrical signals, photographs, ocean waves — can be broken down into lots of smaller oscillating signals, each with completely regular periods, as shown in the video below.

The benefit of breaking a complicated signal into lots of small regular ones is that you can then analyze each of them individually to learn about how the big picture signal arises.

In their study, Burnett and Hayne broke down Europa’s hemispheric dichotomy into two oscillating pieces: one piece that oscillated as if Europa’s rotation has always (or at least for a long time) been synchronous and another piece for any non-synchronous rotation. The figure below shows the result of their analysis.

They found that the Fourier term for non-synchronous rotation was much smaller than the term involving only synchronous rotation, meaning that any non-sychronous rotation must have been very small.

How small? Estimating the rate of non-synchronous rotation requires have some feature on Europa’s surface whose age is known. Thankfully, a cosmic collision provides one such feature.

Puzzled by Pwyll

Europa’s surface is geologically very young, probably less than 200 million years old. We can tell that because, unlike Earth’s moon, the surface of this moon is almost bereft of impact craters: the older a solid surface is geologically, the more asteroids and comets have left their marks on the surface.

If a planet or satellite experiences wide-spread volcanism or other geological activity, that can cover up any impact craters. Indeed, there is evidence that Europa’s sub-surface ocean periodically breaks through the icy crust, potentially erasing impact craters and renewing the surface.

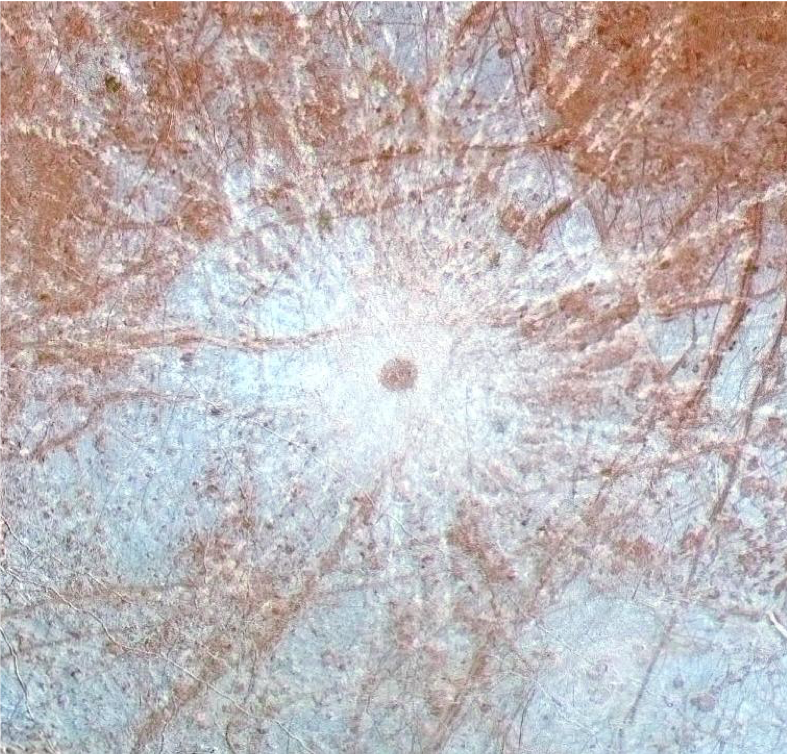

However, Europa does host a few craters and few so spectacular as Pwyll, a 40-km icy splat mark smack in the middle of Europa’s trailing hemisphere. Pwyll’s bright impact rays contrast vividly against the splotchy trailing hemisphere. That means the sputtering process which darkens the rest of the hemisphere hasn’t completely obscured Pwyll yet.

In their study, Burnett and Hayne estimate that Pywll is about 1 million years old, a geological newborn, and therefore the darkening process must take at least 1 million years to darken a fresh surface on Europa.

Given how small the non-synchronous Fourier term is, this age estimate translates into a non-sychronous rotation period of almost 1 billion years. In other words, the two hemispheres can’t reverse more often than once every 500 million years — a very long time.

So how to reconcile this result with the apparent requirement for non-synchronous rotation from the cycloidal analysis? Burnett and Hayne can only shrug and say it’s a puzzle.

We’ll just have to send a probe to Europa to find out.