Introduction to Perseverance – https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/edu/news/2020/6/17/meet-nasas-next-mars-rover-perseverance-launching-this-summer/

Uncategorized

Even though the New Horizons Mission completed its flyby of the Pluto system more than four years ago, analyses of the treasure-trove of data returned continue to reveal how complex and colorful this system really is.

In our research group meeting today, we discussed a recently published analysis of landslides observed on Pluto’s moon Charon from Chloe Beddingfield of the SETI Institute. (Before continuing, let’s just pause for one second to reflect on the fact that we can talk about catastrophic geological events on a world almost 8 billion kilometers from Earth …)

Discovered in the 1978, Charon is the largest of Pluto’s five moons, about a third the radius of our Moon, and is made of about half rock and half ice.

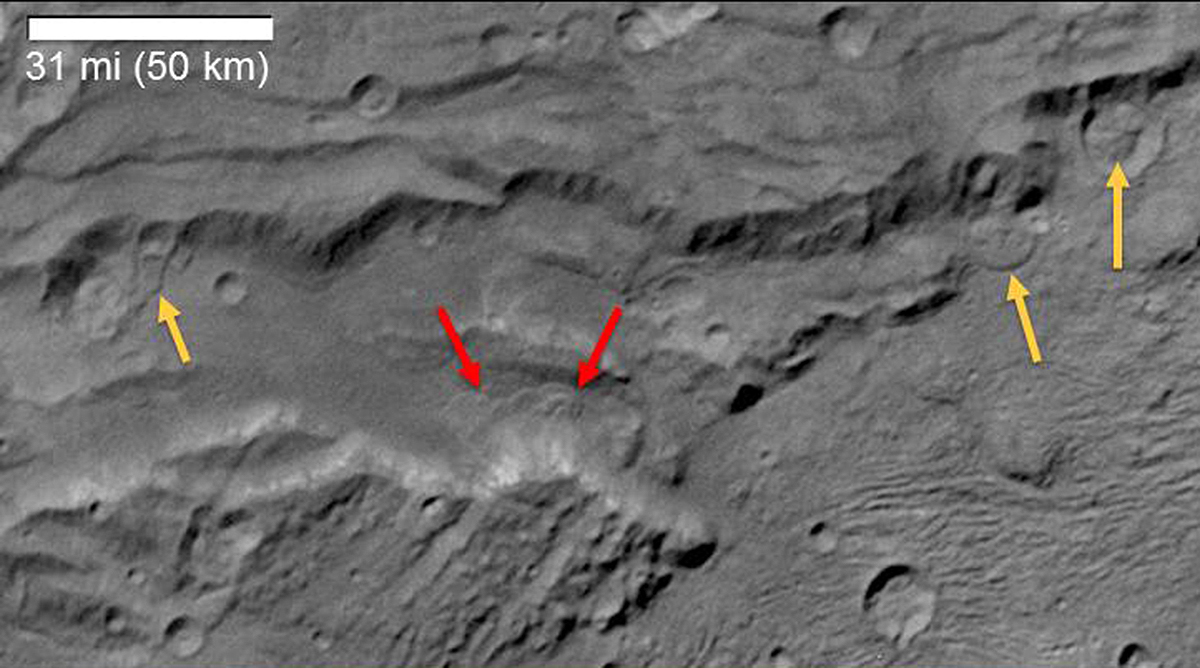

As New Horizons zipped past the Pluto system back in 2015, it snapped lots of relatively high resolution photos of Charon’s surface, revealing an icy surface covered in craters, ridges, faults, and other weird geological features we don’t understand.

Among these striking features, landslides stood out prominently. Landslides on Earth often happen when an unstable hill or ridge becomes saturated after a rainstorm (as happened a few years ago in Boise).

On Charon, though, there is no rain (or atmosphere for that matter), so the landslides there probably occurred as the result of seismic activity, that is, a moonquake.

An enduring mystery of terrestrial and extraterrestrial landslides alike is why they are able to run out for such long distances even though they don’t fall very far.

These very long landslides are unimaginatively called long runout landslides. The Blackhawk Landslide in the San Bernardino mountains, for example, fell about 1 km but ran out for more than 8 km. Scientists have speculated the landslides may be cushioned by a layer of trapped air, which reduces friction as they rumble along.

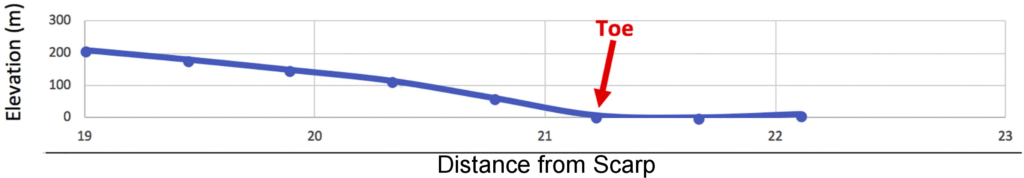

Since it has no atmosphere, Charon’s landslides can’t be cushioned by air, and so Beddingfield and colleagues set out to determine whether these landslides are also anomalously long. By carefully mapping the landslides’ topographic profiles using New Horizon’s imagery and altimetry data, they found the landslides ran out between two and four times farther than they should have, based on the available gravitational energy.

These results confirm that long run-out landslides have made the long run-out all the way to the Pluto system, and something besides atmospheric cushions must be responsible. Other explanations include powerful sound waves carried along by the tumbling debris itself, a hypothesis called acoustic fluidization — which would be a great geology-based cover band name.

This study shows us we still have a lot of learn about the most distant objects in our solar system. Even though Charon may be the moon of a dwarf planet, it seems to have the same geological potency of a full-sized planet.

As you may have heard, exoplaneteers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz shared this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics for the first discovery of an extrasolar planet around a Sun-like star.

These discoveries are now so commonplace, with thousands of exoplanets now known, it’s hard to remember back when each individual discovery was groundbreaking. So to reflect on how far we’ve come, we went back to Mayor and Queloz’s original 51 Peg b discovery paper at our research group meeting on Friday.

Even after decades of exoplanet discoveries, their paper is a gem, with bold scientific claims buttressed by meticulous observational data. As a gas giant circling its host star every 4 days, 51 Peg b presented a clear challenge to our notions of planet formation which said gas planets like Jupiter can only form very far from their host stars. Even so, Mayor and Queloz built a nearly bullet-proof argument for their discovery, and their results were confirmed within a week of their announcement.

But re-reading the paper this week, I was especially struck by how much our understanding of exoplanetary systems has changed and how many of their arguments, perfectly plausible at the dawn of exoplanet science, have been turned on their head — literally.

A Wobbly Rainbow

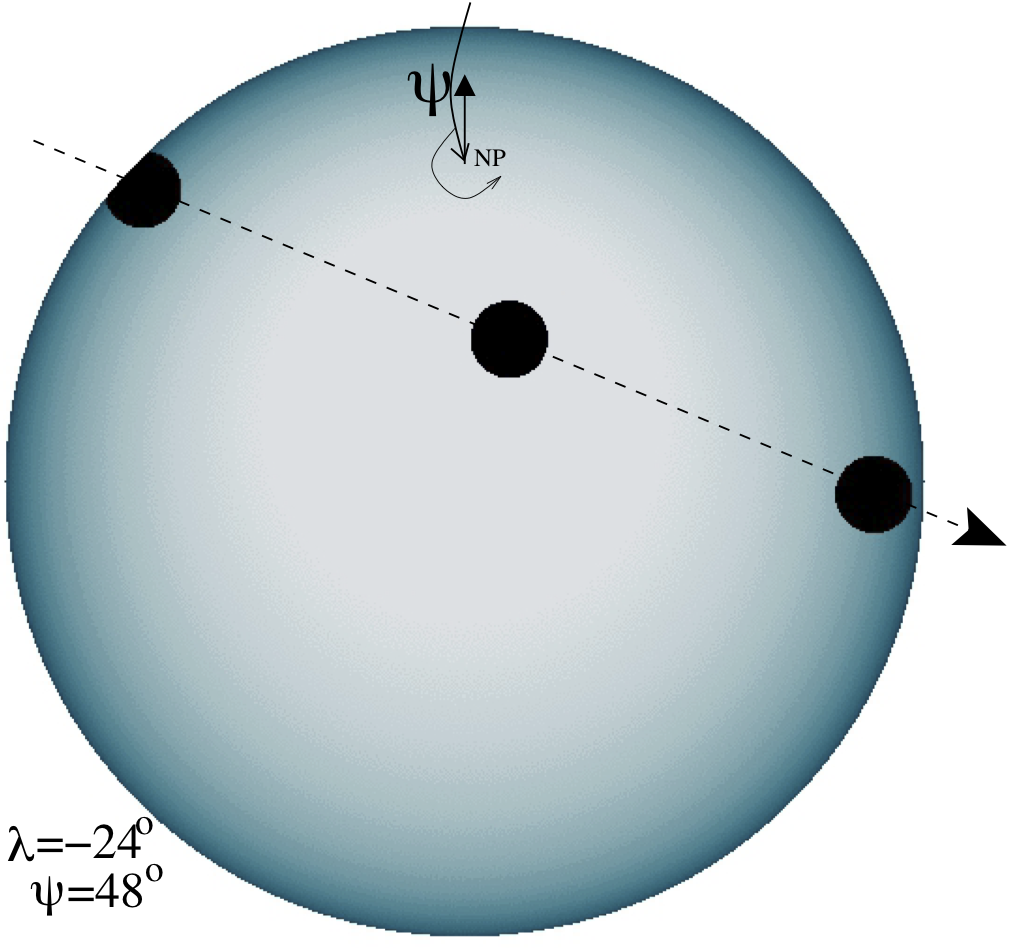

To find 51 Peg b, Mayor and Queloz used what has now become a standard exoplanet discovery technique, radial velocity measurements. The animation above shows how this works: as a planet circles its host star, the star also revolves around the planet. If the planet’s orbit is not too far from edge-on as seen from Earth, the Doppler effect will raise or lower the pitch (i.e., color) of the star’s spectral features as the star pirouettes toward and away from Earth.

With this technique, Mayor and Queloz detected the teeny gravitational tug of 51 Peg b on its host star to find the planet and estimate its mass (about half Jupiter’s).

As powerful as this technique is, though, if the planet’s orbit is not exactly edge-on as seen from Earth, the mass inferred is smaller than the actual mass. And so when Mayor and Queloz detected 51 Peg’s gravitational gumboot, they couldn’t be sure whether they had detected a gas giant in an orbit nearly edge-on or a small star in an orbit nearly face-on.

To address this uncertainty, Mayor and Queloz measured the star’s rotation and found the equator was nearly edge-on to Earth. Since the orbits for solar system planets are all nearly aligned with the Sun’s equator, it seemed obvious that 51 Peg b’s was as well.

So the inferred radial velocity mass must be close to the actual mass, and spectral oscillations were caused by a planet.

Marvelous Misalignment

Later observations of 51 Peg b confirmed this alignment assumption. But we now know that many exoplanet orbits are severely misaligned compared to their stars’ equators. In some cases, the planets actually orbit at a right angle or even in the opposite direction to their stars’ rotation.

The reasons for these misalignments are not clear — in some cases, the stars might undergo an early phase of chaotic rotational evolution. In other cases, the planets might start out in well-aligned orbits, but gravitational interactions among planets or with a distant star can produce misalignment.

It Could (and Did) Happen Here

Even though 51 Peg b seems not to have experienced this misalignment, its discovery forced astronomers to reconsider the canonical wisdom of planet formation and think outside of the box about where we might find planets. Once it became clear that Jupiter-sized planets could occupy very short-period orbits, radial velocity observers sifted their data again and found dozens of planetary signals hiding where no one had thought to look before.

And the dramatic orbital evolution later invoked to explain 51 Peg b’s very small orbit prompted astronomers to re-visit previously puzzling aspects of our own solar system. Now we think the same kinds of prepubescent shake-ups that occur regularly in extrasolar systems probably also happened here, perhaps explaining why Mars is so much smaller than Earth and unlikely arrangements of orbits in the Kuiper Belt.

51 Peg b’s Legacy

51 Peg b is sometimes mistakenly called the first exoplanet discovered, but, in fact, the first confirmed exoplanet system was discovered in 1992 orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12. However, as the first planet orbiting a Sun-like star, 51 Peg b definitively demonstrated the existence of planetary systems resembling our own.

And here, 25 years after its discovery, we know planetary systems are common, with on average at least one planet for every star in our galaxy. The awarding of the Nobel Prize to Mayor and Queloz (as flawed as the Nobel awards are) is a rightful recognition of the profound importance of their work. Indeed, the discovery of 51 Peg b was not just a stunning testament to human achievement — it’s a response to the age-old question, “Are we alone in the Universe?”. Each exoplanet discovery since then whispers the answer, “No, we are not.“